Art and Craft in glass

The story of the stained glass windows in Sturminster Newton’s St Mary’s Church is also an important part of the history of women, says Michael Handy

Published in November ’19

THE WORDS ‘radical innovation’ and ‘illustrated church windows’ may not be the most natural partners in many people’s minds, but Dorset in general and Sturminster Newton in particular have genuine reason to associate them. There’s Laurence Whistler’s beautiful engraved windows at Moreton, the agricultural stained glass window in Mosterton’s church of St Mary and, at its namesake in Sturminster Newton, two windows by Britain’s first female maker of stained glass windows: Mary Lowndes.

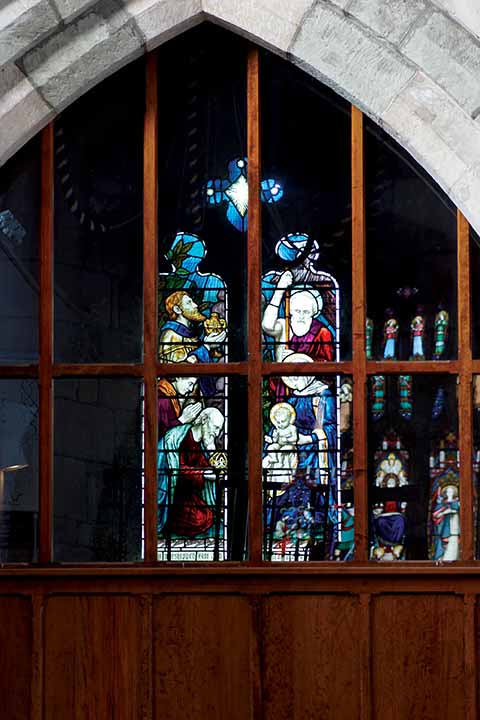

Mary Lowndes devoted her life to stained glass window-making. The two windows of hers in St Mary’s Church were the most important she ever made as they were dedicated to her mother, Elizabeth Lowndes, and her father, Canon Richard Lowndes, vicar of St Mary’s for 36 years. The first window that she made for the church was commissioned by her father. Featuring the Nativity, it is in the West Tower and is of a conventional stained glass design. Her second window, the South Chapel’s window showing the Resurrection, is a pure ‘Arts and Crafts’ design, reflecting the influence of her London training and apprenticeship.

She was Dorset born and bred, attended Slade School of Art in London from 1883 and became a pupil of Henry Holiday, with whom she first worked cartooning. The word ‘cartoon’ comes from the Italian cartone (a stiff paper) and the act of cartooning is drawing the design of a piece to the same size of the final work on stout paper.

Mary established herself for a while at Britten & Gilsen, at whose premises in Southwark Street, London, she had a glass-painting studio. Indeed, it was there that the Nativity window was designed and made. A characteristic of her windows at this date was the slab glass (panes of uneven thickness and great colour) which had been developed by Britten & Gilsen. Coincidentally, it is also the material used by the Irish stained glass window-maker, Harry Clarke, which he used in his Art Deco memorial window in St Mary’s, Sturminster. Clarke was a devout Roman Catholic, and this is the only piece of his work in an Anglican church.

Also working at Southwark Street when Mary was there was Christopher Whall, then beginning to establish his position as the leading stained glass artist in the Arts and Crafts movement. His ideas had a significant influence on Mary’s future work, as can be seen in her Resurrection window, which was made in co-operation with the illustrator, Isobel Gloag.

As well as being a creative force in her own right, Mary also wanted to allow others to pursue her path, without having the restrictions of large commercial studios or the overhead of employing their own team of craftsmen. In 1897, in partnership with Alfred J. Drury (former head glazier of Britten & Gilsen) she set up the firm of Lowndes and Drury, Stained Glass Workers, at 35 Park Walk in Chelsea. They employed a permanent staff of cutters, glaziers and kiln men with whom any artist who wished to create a window could work, supervising the whole process of carrying out a design in glass, then paying for the services and materials used from their fee for the commission.

The venture was a success from the outset and in 1906 moved from its cramped Park Walk premises to purpose-built studios and workshops known as The Glass House in Lettice Street, Fulham. Mary’s enterprise was a deliberate encouragement to women to take up the craft, and from the early 1900s many women, trained at the Royal College of Art by Christopher Whall, and at the London County Council’s Central School of Arts and Crafts, came to work at The Glass House.

That success all started with the Nativity window at St Mary’s. It is a relatively small window and, as Nancy Armstrong FRSA, who wrote a pamphlet about Lowndes for the church, puts it, ‘Mary’s father did her no favours when allowing her to put the “Nativity” in the West Tower, newly opened up (in 1884) when the nave, aisles and transepts received their present seating. Technically it was an abominable site. It is so high it is difficult to see. Should you stand beneath the window the angle is too acute: should you stand further into the church you find the glazed doors obscuring the view and when you stand even further down the nave, a) the window is too far away to see either the details or the dedication and b) the cluster of bell ropes hang in an organised bunch in front of it….

‘However, Mary Lowndes worked her perspective with care. The design is neat, making full use of the space provided. By having all but one of the heads looking downwards, she both creates an artistic tension as well as making the scene appear very personal – as if all the characters were attending not only to the Child but also to the observer him/herself. She especially stressed the importance of life drawing, feeling it was an antidote to the “ecclesiastical tailors dummy” in late Victorian “trade” windows [as can be seen in churches renovated in this period]. The well-balanced colours of her composition are very penetrating, especially when the window is seen as the sun is setting. The reds disappear first, then the pinky-mauves (known as “gold-pink” because the colouring agent in the molten glass is gold dust – used almost exclusively by Arts and Crafts artists), finally the greens and blues, leaving the Child and other white areas the last to be seen. As the sun finally sinks the big star in the canopy above still shimmers and trembles, assuring us that “…in the West lies the future” through the birth and life of Jesus Christ.’

When you look at the Resurrection window, it is hard to believe that only six years passed between the Nativity window’s creation and this one. Nancy Armstrong again gives details of its back-story, suggesting that it ‘shows a pure Arts and Crafts design palette of colours and display of detail – all of which (had) to be more expensive than “trade” windows. The love of detail is also testament to the lively process of research, into the attributes of saints and historical figures, into authentic representation of costume or architectural and landscape settings, and into flora and fauna associated with particular charters or incidents.’

Woven into all the above is the inspiration for her window: Mary’s father. At the base of the three-light window is the following dedication: TO THE GLORY OF GOD/AND IN LOVING MEMORY/OF RICHARD LOWNDES/WHO SERVED HIS PARISH/IN THE OFFICE AND WORK/OF A PRIEST IN THE/CHURCH OF GOD FOR/THIRTY SIX YEARS. CALLED/TO HIS REST OCT 3RD 1898.

Mary designed and made well over a hundred windows between the 1880s and her retirement in the 1920s. A few were in collaboration with other artists, such as Isobel Gloag and the painter, Emily Ford, not only for churches but also for houses and commercial premises. In Victorian times, Mary was what would have been referred to as a confirmed spinster, and her style of dress while painting or creating stained glass looks as if it could have come out of the wardrobe department of the series Gentleman Jack, which was shown this year on television.

Her political life, too, was full: amongst other positions, she was Chairman of the Artists’ Suffrage League and a committee member of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage and she took a leading role in 1909 in the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Congress in London.

She was an important figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, but just as important is the fact that she was one of the very first women to embark on a full-time career as a stained glass artist and craftswoman. The two windows in Sturminster Newton by her are not just important pieces in their own right, but are possibly the most vulnerable, personal and interesting of all her work.