Two sieges and a safeguard

Rachel Hassall relates the story of how Sherborne’s castles old and new fared in the Civil War

Published in October ’19

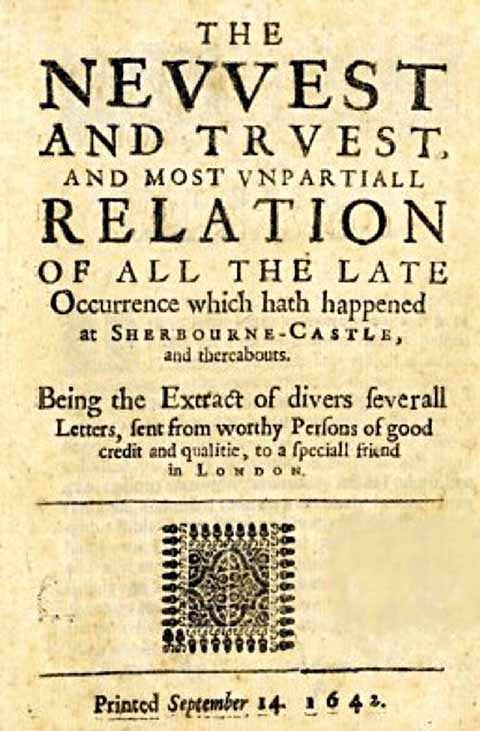

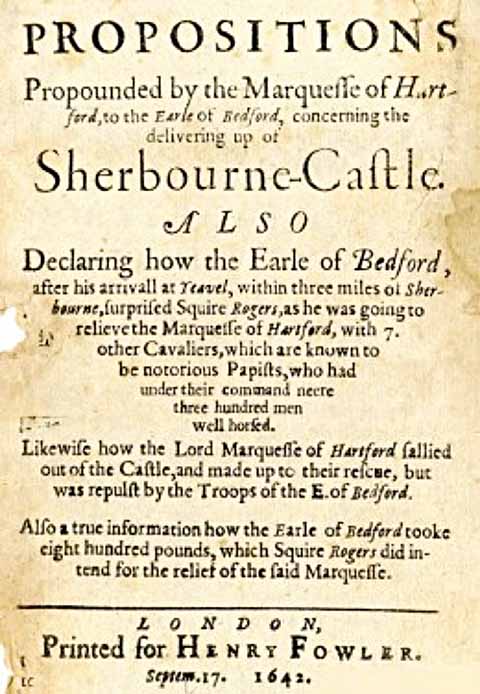

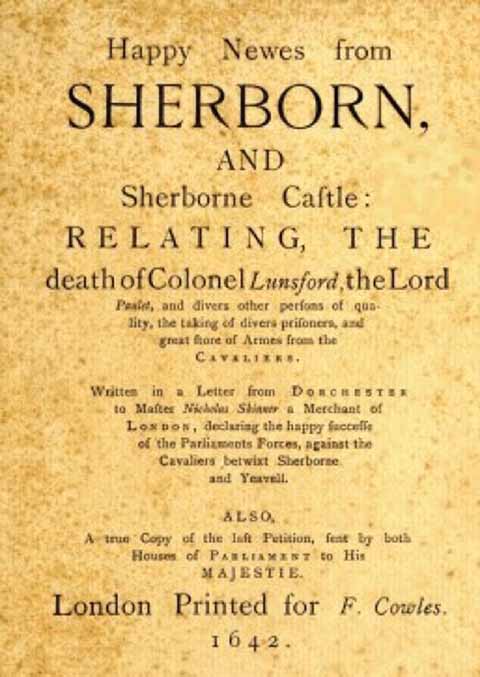

Three Civil War era pamphlets from the Sherborne School archive. The tone of the pamphlets is immoderate to say the least.

At the crossroads of the main north/south route from Bristol to Weymouth and the east/west route from London to Exeter stands the town of Sherborne. Its position gave it strategic importance during the English Civil War (1642-1651) and the traditionally Royalist area saw a lot of action.

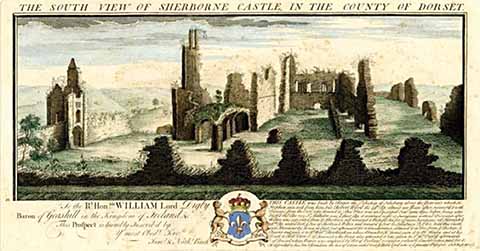

On 5 August 1642, the King’s commander in the south-west, William Seymour 2nd Marquess of Hertford (1588-1660), arrived in Sherborne with Sir Ralph Hopton and 400 horse. They garrisoned the Old Castle, where they were joined by local Royalist gentry with 400 foot.

On 2 September 1642, a Parliamentarian force, commanded by William Russell 5th Earl of Bedford (1616-1700), marched from Yeovil and encamped on the high ground north of Sherborne (still known as ‘Bedford’s Camp’). From here, Bedford’s artillery bombarded the Old Castle and the town (aiming at the ‘church steeple’) but caused little serious damage. In response, Hopton fired cannon into Bedford’s camp for three nights, with the result that 800 of Bedford’s troops are said to have deserted. Bedford abandoned the siege and on 6 September retreated to Yeovil. Hopton, with 100 horse, 60 dragoons, and 200 musketeers, followed and a minor skirmish (known as the Battle of Babylon Hill) took place to the west of the town, near the present-day A30, with the result that Hopton lost about 20 of his men and retreated to Sherborne.

Emboldened by his defeat of Hopton’s forces, Bedford, now armed with ‘three great brass pieces’, marched back to Sherborne and resumed his siege of the Old Castle. When a shot demolished a section of the curtain wall, the Royalists sounded a parley and fired an arrow over the wall with their terms of surrender attached to it. Hertford agreed to surrender the castle providing the safety of his ‘great-spirited little army’ was guaranteed. On 20 September 1642, he withdrew to South Wales. The Parliamentarian forces held the Old Castle until they were driven out by a Royalist force on 12 February 1643.

On 1 August 1645, Parliamentarian forces commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671) again besieged Sherborne Old Castle, now commanded by Sir Lewis Dyve (1599-1669). This second and last siege lasted sixteen days and, following heavy bombardment and mining, Dyve surrendered the castle on 17 August 1645. The castle was slighted in October 1645.

The Parliamentarian forces requisitioned Sherborne Abbey and the school buildings for use as barracks and the Schoolroom as a guardroom. In August 1650, the school governors were ordered by Captain Helyar to take down the royal arms over the entrance to the Schoolroom and on the south wall of the Headmaster’s house (now the Lady Chapel of Sherborne Abbey). They were hidden away and replaced soon after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Brothers in law, but adversaries in arms: on the left is George, Lord Digby, on the right is his wife’s brother, William, Earl of Bedford. Credit: Courtesy of Sherborne Castle Estates

Three contemporary documents in the Sherborne School archives tell the story of the first siege of Sherborne Old Castle in September 1642, from both the Royalist and Parliamentarian perspectives. There is more than a whiff of propaganda about all of them. The first is modestly titled: The newest and truest, and most unpartiall relation of all the late occurrence which hath happened at Sherbourne Castle, and thereabouts (printed 14 September 1642).

‘On this day sennight being Saterday, the Earl of Bedford appeared before Sherborn Castle, His Forces consisted partly of Devonshire men (whereof some 400 came to Dorchester on Tuesday last as I take it, but sure I am, a Minister rode very demurely before them with a Bible in his hand, and many of them by their habit were judged men of good qualitie) as also men of Dorset and Sommersetshire. Many of them advanced slowly and sadly, and you know the Nature of West-countrey men, who most of them holding their means for their lives, were loath to hazard their lives and lifelyhood at one adventure.

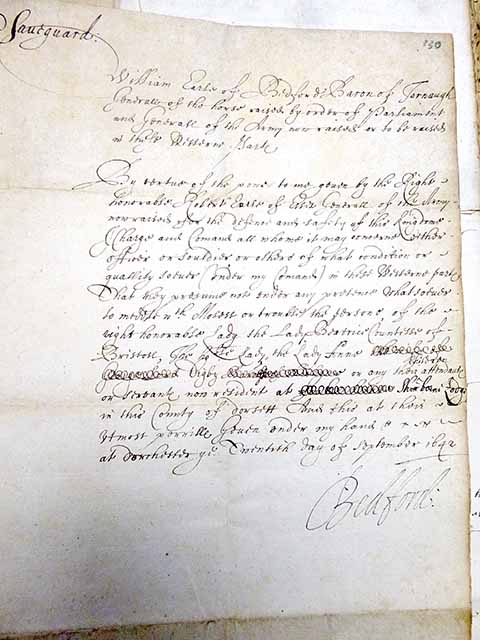

The ‘Saveguard’ letter extracted from the Parliamentarian Earl of Bedford by his sister, Anne, whose husband George, Lord Digby supported the King’s cause. Crredit: Courtesy of Sherborne Castle Estates

‘The men of the Town of Sherborn (presumed to be of the Earl of Bedfords side) declared themselves otherwise, and with their shot did much annoyance to his men. There hath passed many skirmishes betwixt the Marquessse of Hartford’s men and the Earl of Bedfords, with the chance of warre; sometimes the one and sometimes the other had the better.

‘At last the Countrey men began to think that Featherbeds were better lodging then the hard earth, which made many of them (if you will have it in the best phrase) withdraw themselves away, which I doubt not but will willingly come back again to see an happy agreement betwixt the King and Parliament. The Earl of Bedford with those that were left, discamped, and retreated to Yevell, (4 little miles from Sherborn) where the Lord Marquesse and the Lord Paulet bid him battell, and there followed an hard and hot encounter, wherein the Marquesse had the best of it.

Yours, A.W.’

There is a further letter, describing among other things the death of ‘a Dorsetshire Gentleman Captain H. Hussey. It reads: ‘Whilst they [the Parliamentary troops] had him at their mercy, they most barbarously cut off his members, and then did him the favour to kill him.’

The defining moment of the siege was described in a pamphlet entitled EXCEEDING JOYFULL NEWS FROM SHERBOURNE CASTLE.

‘After some 40 shots made by the Earle of Bedford against the Castle, a fortunate shot was made, which tooke away the main battlements of the Castle, where one of the pieces was planted, so that the ordnance fell to the ground with a great part of the wall, which was weakened by the often batteries of our canons, which shot put the Cavaliers into such a fright, that suddainly a trumpeter appeared upon the wall sounding a parley, which was answered by the Earle of Bedford, and a trumpet sent to demand the reason of that suddan parley, who coming up to the mote, there was a paper fastned to an arrow shot over to him; with a direction to the Earle of Bedford, which he taking, returned back to our Army, and delivered the same to the said Earle.’

The Civil War was not just about armies, though; there were families riven by their allegiance to the opposing factions. George, Lord Digby and William, Earl of Bedford were brothers-in-law; George was married to Lady Anne Russell, Bedford’s sister. In a picture painted in about 1632, George, on the left, is shown as a man of learning with papers and an armillary sphere (used in astrology) at his side. William is depicted as a military man, with an aggressive stance and armour at his feet. During the Civil War, though, George proved himself a better military commander than William and became Secretary of State to Charles I, accompanying him at all the major battles.

When William camped his Parliamentarian army outside Sherborne, he threatened Sherborne Lodge (the present castle), where his sister was living with her children and mother-in-law. It was a family home with large windows and no fortifications. It was virtually indefensible. Lady Anne is reputed to have sent word to her brother that if he persisted in his hostile intentions, he would find his sister’s bones in the ruins.

She extracted from him a document, which safeguards the occupants of Sherborne Lodge. Its key passage is: ‘By vertue of the power to me geven by the Right Honorable Robert Earle of Essex, Generall of the Army now raised for the defence and safety of this Kingdome, I Charge and Comand all whome it may concerne, either officer or souldier or others of what condition or quallity soever (under my Comand) in these Westerne parts, That they presume not under any pretence whatsoever to meddle with, Molest or trouble the persone of the right honorable Lady, the Lady Beatrice Countesse of Bristoll, The honble Lady, the Lady Anne Digby or any their children, attendants or servants now resident at Sherborne Lodge in this County of Dorsett, And this at their utmost perrill. Geven under my hand at Dorchester the Twentith day of September 1642

Bedford.’

Thus was what is now Sherborne Castle saved for posterity.