Our man at Number 10

As we mark 80 years since the outbreak of war, Roger Guttridge recalls his interview with Neville Chamberlain’s private secretary

Published in September ’19

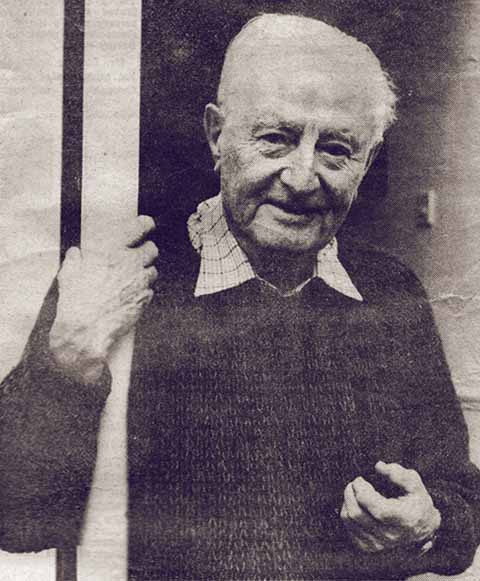

By the time I met Jasper Rootham in 1985, he was one of only two people still alive who was inside 10 Downing Street on the historic night that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain famously waved his Munich document and declared that he’d secured ‘peace with honour’. He was there again a year later when war was declared.

I met Jasper at the launch of his ninth book, Lament for a Dead Sculptor and Other Poems. It included a section called Poems from Wimborne, written since his retirement to West Street a few years earlier. But however good the poetry, I realised when chatting to him that there was a bigger story awaiting my pen.

At the time of the Munich declaration in September 1938, Jasper – then aged 28 – had been on Chamberlain’s staff just three days.

‘I was there when he came back with that piece of paper,’ he told me. ‘I was in the hall at Number 10 when he went on to the balcony. All his ministers were there. I looked at them all and knew there was only one who was going to resign and that was Duff Cooper.’

Cooper, arch-critic of appeasement, duly left the Cabinet. Jasper had his own views but, as the Downing Street new boy, kept them to himself.

‘In most cases the feeling was one of enormous relief but I thought we should have declared war,’ he said. ‘I had spent a lot of time in Germany and had seen what the Nazis were like. I didn’t want to live in a world dominated by Hitler. As an individual, I wanted to have a go but my loyalty was to the Prime Minister I was serving so I didn’t talk about it.’

Jasper was the duty private secretary when, in March 1939, Mussolini invaded Albania and Hitler waded into Czechoslovakia and Austria. ‘I was directly involved in that. I was at Number 10 when Ministers were scurrying in and out.’

Britain declared war on 3 September 1939 – and in a later interview, Jasper revealed that the French almost backed out of the declaration the previous day despite mobilising their forces following Hitler’s invasion of Poland. At the time Jasper was one of only three men who knew this.

‘The only record of this is a note I made listening in on the telephone and writing down from French into English what the French foreign minister said and what our Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax said in return,’ he recalled. The news was conveyed to Chamberlain, who immediately informed the Commons.

‘There was uproar in the House. Chamberlain sounded to them very lame and the facts were an appeasement. He was told, “For God’s sake, speak for England.”’ Jasper and the PM left the House pursued by furious politicians. ‘The next thing I knew, half the Cabinet was knocking on my door saying they wanted to see the PM. They were very angry. They all thought there was going to be a declaration of war but they hadn’t had it.’ After an eleventh-hour crisis meeting, it was decided the PM would declare war the following day whether the French did or not.

Within a day or two there was an air raid warning, sparked by a pilot flying from France to England in a private plane. ‘I was in charge of the air raid precautions and we went down into the shelter at Number 10,’ he said. ‘It wasn’t a very good shelter. It wouldn’t have withstood a direct hit.’

As soon as it was decently possible, Jasper told Chamberlain he wished to join the forces and do his bit. But the PM said his duty was to remain at his post. ‘I made it very clear I didn’t agree so to get an awkward chap out of the way, they promoted me and sent me back to the Treasury as Principal.’

Jasper eventually prised himself away from the Civil Service in 1941 and served with the Royal Armoured Corps and the Special Operations Executive.

During my 1985 interview for the Bournemouth Evening Echo, Jasper also confessed to a rare additional talent – the ability to stand on his head. He was demonstrating this to a fellow private secretary in an office at Number 10 when Chamberlain walked in. Reacting as if everything was normal, the PM looked at the upturned civil servant and calmly said: ‘I would like my Foreign Office telegrams when you have finished.’

Jasper told me: ‘When I took the telegrams up to him, he just looked at me, didn’t quite wink and said thank you. He had a sardonic sense of humour.’

Jasper – son of composer Cyril Rootham – described Chamberlain as a ‘frightfully good master’ and ‘extremely methodical’. ‘I was very fond of him,’ he said. ‘He was a very brave and very civilised man. He liked all the same sorts of things that I like – such as classical music, literature and wildlife. He had an admirable brain and was a very good administrator.’

Jasper, who also worked under Winston Churchill before joining the forces, added: ‘The one thing Chamberlain didn’t have which Churchill did – and Churchill was almost unique in this – was an enormous sense of history and a breadth of vision. Churchill was an exasperating man in my view but Chamberlain was not at all.’

Jasper died in 1990 aged 80. His lifelong friend Enoch Powell gave an address at his funeral in Wimborne.