Harry Paye: pirate of Poole

Nick Churchill looks back 600 years to a redoubtable son of Poole

Published in June ’19

Cannons fired on the hour, a parade of Pirates through the streets of Poole, live music and sea shanties on two stages on the Quay, fairground rides, lots of stalls, a children’s pirate costume competition, a fire-eater, a Pirate Trial, in fact all manner of piratical shenanigans in fancy dress – just what the blazes is going on?

The answer is Harry Paye Day, when Poole celebrates its best-known pirate, Harry Paye, who died 600 years ago this year.

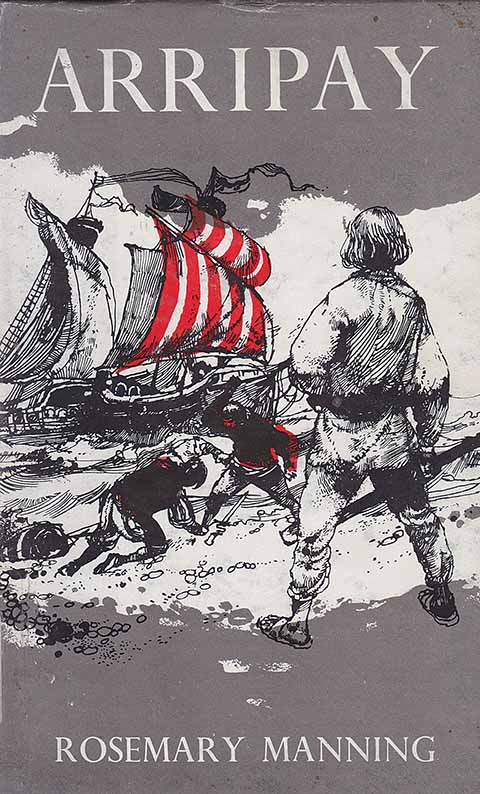

Actual details of Harry’s life are scant and his story has been much mythologised, not least in Rosemary Manning’s rollicking 1963 historical novel, Arripaye, but tradition has it that he was born in Poole around 1360 in a house at the junction of Hill Street and Carters Lane, where there is now an electricity substation. Although there is some record of his father, no other Payes are linked to Poole at that time. Nonetheless, it is certain that Harry used the town as a base for a range of maritime activities that included the ferrying of pilgrims to Galicia to visit the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in his ship, the Mary.

The Harry Paye commemorative plate by Poole Pottery is from 1977 and was created by Karen Hickisson. Not a great deal is known for certain about Harry, but he was a contemporary of Poole’s earliest known mayor, Thomas Canawey, who’s only known about because he was named as a suspected pirate in 1408.

The Mary was a sizeable ship for its time, licensed to carry 80 pilgrims, presumably with room for their transport animals as well as its own crew, but not every outward journey to Galicia was matched by a similar payload of pilgrims on the return. Any shipowner will tell you that empty space on a vessel is bad business, so Harry used his initiative to fill the holds of the Mary as she sailed back to Poole, raiding French and Spanish coastal towns and preying on ships in the English Channel. He captured crews and cargo at will, redeeming the former for cash and selling or stashing the latter for further personal gain.

On one trip back from Galicia, probably in 1398, the Count of Gijon employed the services of Harry and his crew in an ongoing conflict with his brother, the King of Castile, who had laid siege to the walled city. According to the story, Harry wasted little time in seizing the Countess and burning Gijon to the ground, possibly under her orders to cover her escape from the Castilian monarch.

In another raid he attacked the western Spanish town of Finisterre and stole a cross from the Church of Santa Maria. What happened to the cross is unknown, but some 610 years later, in 2008, a group of Poole divers including Dai Watkins, Poole Museum’s history manager, who has researched the legends of Harry Paye extensively at home and abroad, travelled to Spain to present the Mayor of Finisterre, Alcado Jose Manuel Traba Fernandez, with an altar cross bearing part of a brass bell recovered from a Spanish ship that had been built in Finisterre and wrecked off the coast of the Scilly Isles. Small recompense, perhaps, but it was gratefully received as some acknowledgement that what might have been perceived as patriotism in Harry Paye’s homeland was, in Spanish eyes at least, untrammelled piracy on the part of the reviled criminal they called Arripaye.

A replica medieval galley in Barcelona Maritime Museum, very probably like those that brought the 1405 invaders to Poole

It is often forgotten that right up to the 17th century, privateers like Harry Paye were given at least tacit permission, and sometimes the Sovereign’s explicit authority, to carry out their rapacious deeds. Thanks to his formidable reputation, Harry was given leave by Henry IV ‘to sail the seas with as many ships, barges and ballingers of war, men-at-arms and bowmen properly equipped to do all the hurt he can to our enemies and for the safety of our realm’ and his loyalty was further demonstrated when he helped suppress the Welsh revolts led by Owain Glynd^wr by defeating a French fleet sent to aid the uprising.

Even so, the line between loyal subject and lawbreaker was a thin one and the King’s ally one day could become his foe the next. So there were times when Harry was called to answer for actions in which, under changing circumstances, he might have been deemed to have gone too far, such as when he was forced to return the ship of a London merchant he had captured in error. More typically, he was fined or ordered to make compensation in kind, although it was often a matter of diplomacy for the authorities to be seen to act.

Rosemary Manning’s really quite bloodthirsty tale of the life and times of a young lad in the service of Harry Paye

In 1404, Harry and his ship were captured by a Norman barge and as the French sailors bound their prisoners and searched the ship, Harry let loose his war cry, signalling to his crew to shake off their shackles and set about their captors. Having dispatched the French and taken their barge, as well as another boat, Harry sailed up the Seine under French colours, raiding as he went.

After 1407, Harry seems to have moved away from Poole, accepted a legitimate position as a commander in the Cinque Ports fleet and lived out his life in Kent, where he married, had a son called Simon and died on 14 March 1419. He is buried in Faversham. None of which prevents the energetic and enthusiastic Pirates of Poole charity fundraisers from celebrating Harry’s legend every June in the annual Harry Paye Day, this year on Saturday 15 June.

The day commemorates Harry’s name while raising money. The ‘spoils’ are shared between local good causes with an additional £500 going to an animal charity in memory of a much-loved Pirate pooch called Louis. This year’s charities are Dorset Children’s Foundation and the Dorset Youth Cancer Trust, both of which serve families in the Poole area. The animal charity is the Staffy and Stray Rescue.

But why should this rather ruffianly figure be so fondly remembered in his home town every year? Maybe the roots of the answer lie in the combined flotilla of four French ships and three Spanish galleys mustered by Charles VI of France and Henry III, king of Castile and León, in 1405 to attack towns along the south coast of England. In September of that year, having raided the Isle of Purbeck where they stole sheep, the armada arrived off Poole.

According to a contemporary account – El Victorial, written by Gutierre Diez de Games, standard bearer to Don Pero Niño, Count of Buelna, like Harry a licensed raider – the invaders were under orders not to plunder, but attacked in force and torched the town before being driven back to their ships by the townsfolk with riders and archers sent from the Manor of Canford. The Spanish then regrouped and, joined by mounted knights from the French ships, resumed the attack.

The people of Poole made their last stand in a warehouse on the Quay – probably the old woolhouse or Town Cellars – before making an escape and retreating as far back as Canford Heath. Perhaps surprisingly, El Victorial mentions only two deaths – a Castilian knight called Juan de Murcia and an unnamed brother of Harry Paye, ‘a good soldier who did very fair deeds before he died’ – despite its note that ‘arrows fell so thick upon the ground that no man could walk without treading on arrows in such number that they picked them up in handfuls.’

Satisfied that vengeance had been taken, the invaders left and made for Southampton. But Harry, who missed the action while undertaking another raid, inevitably sought revenge and the following year, with just fifteen ships at his command, exacted his own ‘Paye-back’, capturing a fleet of 120 French vessels off the coast of Brittany and their cargo of iron, salt, oil and Rochelle claret wine. Returning to Poole in triumph, Harry bestowed his prizes on the townsfolk who, legend has it, were drunk for a month – and that, perhaps, is the reason why Harry’s name remains forever in Poole hearts.

• www.piratesofpoole.co.uk