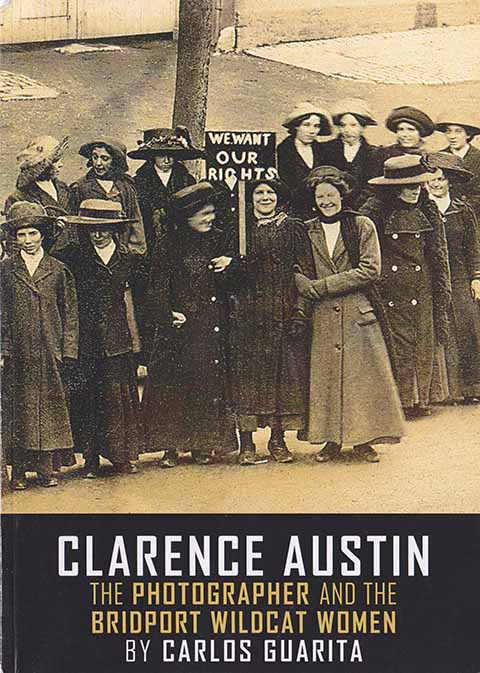

‘We want our rights’

Teresa Rabbetts on a long-forgotten industrial action in Bridport

Published in January ’19

In February 1912, an event took place in Bridport which might be thought of as being uncharacteristically radical for the town: a group of young female workers staged a ‘wildcat’ strike action. It was an incident that was of public interest locally and nationally, but was resolved in a matter of days and then apparently overlooked for the best part of a hundred years. Nonetheless, it was a significant episode in the history of industrial and social reform in Dorset.

By the early part of the 20th century, Britain was no longer the dominant capitalist economy on the world stage. Historians often refer to the years leading up to World War 1 as the ‘Great Unrest’; as the economy declined, the division of wealth grew, leading to a steady fall in the real value of wages and extreme poverty and exploitation for the British workforce. There were waves of strikes, industrial conflicts and riots across the country and a rapid growth in trade unionism.

The turn of the century also saw an upsurge in the efforts of women to attain a more equitable society for themselves: both on the domestic front, against paternalistic attitudes in the home, and nationally. They formed themselves into trade unions, sought to have a respected voice in collective debates on social and economic change and demanded to be given the vote. As rumbling dissatisfaction and discontent formed itself into a more organised campaign, female activists undertook more radical activities.

The Hope & Anchor, where a large group of women employees met; by the end of the evening most of the girls had joined the National Federation of Women Workers

While the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) were becoming increasingly militant and pursuing headline-grabbing activities in London, there were women all round the country who were quietly involved in playing a part in the movement for reform. The West Dorset Women’s Suffrage Society (WDWSS) was an active force, although not always reported on in very favourable terms by the Bridport News; they were in fact a moderate band who advocated non-violent action.

Another Clarence Austin image of the striking girls. The youth of some of the workers is evident in this shot. Credit: Graham Burridge Collection

Bridport, like most other small industrial towns, was built around and dominated by one industry: rope and net. Frequently, whole families worked in the mills, factories, workshops, warehouses and offices of the different rope and net companies in the town. Despite industrialisation from the late 18th century, much of the more specialised net work was still carried out by hand and often in homes by outworkers, with different villages specialising in certain types of net. Most hand braiders were women who produced fine specialised nets and those of a more complicated design, and applied the finishing touches such as hand-sewn edges or attaching ropes, floats and sinkers. The women of Bridport worked hard to make ends meet, not only running the household and caring for their children but also pursuing their own employment while coping with such low wages that households were invariably multi-generational by necessity – every member’s wage was essential to the survival of the family.

Bridport was not a renowned venue for industrial discontent and it is tempting to think that perhaps the women of Bridport, represented by the moderate WDWSS, remote from the headline activities of the Women’s Movement in the capital and the industrial unrest around the country, were too busy working, keeping their families together and surviving their hand-to-mouth existence to protest about their plight. However, in February 1912, a group of female employees were seen outside Messrs Gundry and Co.’s factory in West Street, displaying a placard printed with the words ‘WE WANT OUR RIGHTS’.

What brought this about was that Gundry and Co., one of the large factories in Bridport, proposed a change to the scale of wages paid to the girls. The Bridport News reported that: ‘The dissatisfaction has arisen among the girls employed on the French net machines, and on Friday afternoon they refused to resume work and came out on strike. The girls complain that the proposed readjustment of the scale will operate most unfairly upon those who are at the present time able to earn fairly good wages.’ The workers had been paid by result or ‘piece work’, which meant, as the Bridport News wrote, that ‘Some of these hands earn from 14s to 16s a week on the best kind of work, whereas others, on a different class of cotton, would not earn more than 6s or 7s’. Gundry’s did not propose to raise the rates of pay of the low-paid girls, but rather to reduce the rate of the higher-paid French net machinists. On 11 February a group of French machine hands walked off their jobs in protest.

A Bridport photographer of the time, Clarence Austin, captured the event in a fascinating series of photographs which retired photographer Carlos Guarita, who researched Austin’s life and work, published as Clarence Austin the Photographer and the Bridport Wildcat Women. Amongst the collection are several photos of the striking women in posed line-up shots and in others there are groups of men and boys in the background, peacefully observing the occasion. One photo held by Bridport Local History Centre has been annotated with the names of the women; unfortunately, the provenance of the annotation cannot be verified, although the names do correspond with women listed as netters in the 1911 census.

In the days that followed, the Bridport News monitored the strike in regular reports referring to the participants as ‘girls’, although not naming any individual striker. Whilst the paper had previously printed unsympathetic views on West Dorset suffrage, it is unlikely that the Bridport News references to ‘girls’ were intended to be condescending because again, a look at the 1911 census confirms that the many of them really were girls: teenagers between 14-19 years of age.

It is interesting to note the camaraderie of the girls’ action, demonstrated by the fact that the lower-paid girls came out on strike together with their higher-paid colleagues. Also significant is that the Bridport News reported many men from factories around town assembled to show support, perhaps demonstrating just how essential the wages of the net workers were to the family unit. Each day the girls paraded through the town singing ‘We won’t give in’ and ‘Shoulder to shoulder’. They assembled outside the closed doors of the Gundry works, where they were cheered by the other hands.

Gundry’s factory manager, Mr Macdonald, made an initial unsuccessful attempt to negotiate with the strikers, and then, on the following Wednesday, met with them again to suggest arbitration proposing as arbiter the banker and Conservative MP for West Dorset, Colonel Robert Williams. The girls rejected the proposal, anxious for someone they could trust to be an impartial negotiator, and remained out on strike.

Later that day, Miss Ada Newton from the National Federation of Women Workers arrived from London and met with the striking girls. Formed in 1906, the NFWW was established to be a co-ordinated union for women frustrated at the fact that existing unions were not open to female members. That evening Miss Newton, a former silk factory-worker herself, gave a speech before a large meeting of women employees in the club room at the Hope and Anchor where she promoted trade unionism; by the end of the evening, the Bridport News reported, ‘practically all the girls joined the Federation.’ The following day Miss Newton and Mr Macdonald met and settled that the girls would return to work at six in the morning the next day.

It would seem that the strike had public support as plenty of financial donations were made to support the strikers and a week later the Bridport News published a letter from Ada Newton in which she thanked the people who had subscribed to aid the striking girls: ‘The amount collected was £9 13s 8d, which has been equally distributed amongst the girls affected.’ At today’s value this equates to approximately £760.

So what did the strike actually achieve? With the action resolved and the strikers returned to work, the local union soon broke down – the union subscription was another financial burden on low-paid workers. However, trade unionism in Bridport was re-activated a short time later and contact with the NFWW re-established after the formation of Bridport Trades and Labour Council in 1913. Two years after the strike, the union organised a concert and social event in the town in which women from the 1912 strike took part.

Finally, it would be good to report that the striking girls received satisfactory wage adjustments, but this does not appear to have been the case; at best, the negotiated settlement achieved a period of notice prior to wage levels being adjusted. The Bridport News reported the settlement in the same spirit of goodwill that seems to have been the feeling of the action: ‘…Miss Newton had an interview with Mr Macdonald, with the result that the strike has been settled, on the basis that the girls return to work this (Friday) morning, at six o’clock, the firm undertaking to give four weeks’ notice of any alteration of pay such notice not to be given before the 31st May. We are glad the dispute has been settled and trust everything will work smoothly and pleasantly in

the future.’