The waterway that wasn’t

Roger Guttridge recalls abortive plans for a Dorset and Somerset Canal

Published in October ’18

It was described over 200 years ago as ‘one of the best conceived undertakings ever designed for the counties of Dorset and Somerset’ and I often ponder on how different much of our county would have been had the Dorset and Somerset Canal been completed. Imagine a waterway from Poole Harbour into Somerset to connect with the Kennet and Avon Canal and on to Bristol.

It almost happened. The first eight miles at the Somerset end were actually constructed before the project ran into trouble. The Dorset and Somerset Inland Navigation, as it was originally known, was conceived in 1792, when canal mania was at its height as an alternative to the long and hazardous sea voyage around Land’s End and the even more challenging overland journey. The proposal was discussed at a public meeting in the Bear Inn, Wincanton, in 1793. Prospective investors believed they could rely on a regular traffic in coal from Bristol and the Somerset coalfields to Dorset and, in the opposite direction, Purbeck clay destined for the Staffordshire potteries. Other anticipated cargoes included freestone and lime from Somerset and timber, slate and wool from Dorset.

The project attracted great interest and subscriptions greatly exceeded the minimum required. A route was drawn up that ran from Bath to Frome (with a branch to the Mendip collieries) and on via Wincanton, Henstridge, Stalbridge, Sturminster Newton, Lydlinch, King’s Stag Bridge, Mappowder, Ansty, Puddletown and Wareham to Poole Harbour.

Wareham people voted to support the route, but in Blandford they had other ideas. A meeting at the Crown declared that the canal would be of greatest benefit to its proprietors and the county if it went from Sturminster Newton to Poole via Blandford and Wimborne rather than Wareham. The Blandford route was finally decided on in 1795, but with branches to Wareham and Hamworthy. The 37 miles from Freshford to Stalbridge was costed at £100,000 and the remaining 33 miles from Stalbridge to Poole at £83,000.

But there was opposition from Dorset landowners, in particular Lord Rivers, who insisted that the canal must not extend ‘beyond some point betwixt Sturminster and Blandford, otherwise withholding his consent’. As a result, a drastic decision was taken to abandon the southern section of the canal, reducing its length to 48 miles and the cost to £146,000.

From the perspective of the 21st century, it seems incredible that the canal would now terminate at Gain’s Cross, south of Shillingstone. Would this not have defeated the original object of creating a link between Poole and Bristol?

The necessary Act of Parliament received Royal Assent in 1796 giving the Dorset and Somerset Canal owners the right to draw water from any source within 2000 yards of their canal and to create a junction with the Kennet and Avon, thus connecting it to the national canal network.

Work on the Mendip collieries branch began at Cote, in the parish of Stratton, but no sooner had the first barge been launched than the scheme ran into the first in a series of financial problems. Of £70,000 pledged by prospective shareholders, only £58,000 was forthcoming. With people now preoccupied by the war with France, the promoters lurched from one crisis to another and managed to complete only eight miles of their canal. Progress was also hampered by the rocky and uneven terrain in the Mendips; those first eight miles required 25 bridges, three tunnels, an aqueduct, twenty stop gates and three balance locks.

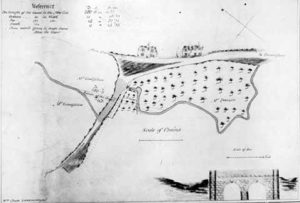

Construction finally ceased in 1803, when the last of the money ran out, although hopes lingered on until the mid-1820s, when attempts were made to involve the canal company in plans for a railway covering the same route. These plans also foundered and it would be another thirty years before the Somerset and Dorset Railway came to fruition. By then the Dorset and Somerset Canal was an eight-mile, overgrown relic. One of the few surviving documents is a plan for a double-arched aqueduct over what is now the A357 road at Fiddleford. It shows a ford where the stone bridge is today and two cottages which still survive. The site is literally a stone’s throw from the present-day Fiddleford Inn. I lived next door to this former brewery in the 1960s and have often tried to imagine it as a canal-side pub serving pints and meals to the crews of passing narrow-boats.

The Waterway that Never Was is one of 35 chapters in Roger Guttridge’s book Dorset: Curious and Surprising (Halsgrove, £9.99).