Look it up in Pevsner

Michael Hill, author of the second edition of The Buildings of England: Dorset talks through his seven-year task to bring the 1972 edition up to date.

Published in May ’18

In 1951 Nikolaus Pevsner, art historian and German émigré, completed Cornwall and Nottinghamshire, the opening volumes of a project intending to describe all ecclesiastical, public and domestic buildings of interest in England, together with the furnishings of churches. The survey, published by Penguin Books, continued, county by county, over the next two decades, with the final volumes (on Oxfordshire and Staffordshire) issued in 1974: 46 books in all. Whilst the earlier counties were written exclusively by Pevsner, increasingly – and to ensure an early completion – co-writers were drawn in, as in the case of Dorset, where John Newman wrote the secular entries for the 1972 edition.

RNLI Lifeboat College, Poole

There are few truly successful modern (in the sense of avant-garde) buildings in Dorset. Often, where it is attempted, traditional townscape is disrupted or destroyed. But this is not so with the RNLI Lifeboat College in Poole, completed in 2004. For a start, its open waterside site invited the bold approach made by Poynton Bradbury Wynter Cole Architects – dramatic, sweeping shapes, highly evocative of sails and sailing. Directly on the harbour-side, framed by the jagged prow-ends of the L-plan main block, is an open-framed rotunda, in the base of which is a café. Another block is linked by a diagonal footbridge, while at the entrance a gate-lodge has an oval plan and slanting roof. Also here is an RNLI memorial by the sculptor Sam Holland, added in 2009, on a plinth (also slanting) designed by Ellis Belk architects. Credit:James O Davies/Yale University Press

It was a tremendous achievement, one that was soon recognised as internationally unique. The ‘Pevsners’, as they are often called, were soon regarded as the most authoritative of architectural reference books, much quoted and argued over. And beyond the recital of date, architect and style, a key feature is the discussion of the character of buildings, and comments on whether they are successful or in some way failures. So not only are buildings of beauty and importance included, but also those that are ugly or even eyesores.

Inevitably, architectural life did not stop once a new volume was issued, and – despite several counties receiving updated editions of limited scope – it was decided that a series of thoroughly revised new editions should be produced, a process that started with the publication of London 2: South in 1983. At the same time, the idea was expanded to include Scotland, Wales and Ireland, with the first two countries completed in 2016 and 2009 respectively. (Ireland remains ongoing.)

In revising each area, newly erected buildings were included, and the most significant demolitions noted, often with regret. The particularly distinctive tours around towns – quaintly called ‘perambulations’ – were adjusted to cope with the comprehensive re-planning of the 1960s and 1970s, while buildings that had previously been missed, or not fully appreciated, were inserted. The opportunity was also taken to improve the illustrations. From 2002 (after the series transferred to Yale University Press), colour photographs were incorporated, and plans of towns and key buildings became a useful practical feature. More space was required for these gains, so the book size was increased from the old, comfortable pocket size to a volume some 8¾ inches high, fitting only the most capacious of pockets!

Grimstone railway viaduct, Stratton

A great many of the finest structures on the Great Western Railway, and those of its associated companies, were designed by its first engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The 1857 short viaduct over the southern end of the Sydling Valley on the Great Western line to Weymouth was most likely his. It is almost a copy of a similar viaduct in Chippenham, built in 1841 for the Great Western main line to Bristol. Loosely modelled on a Roman triumphal arch, there is the added refinement of a row of four small transverse arches running between the main arch and the pair of side-arches. Transport-related buildings such as this were often ignored in the earlier editions of Pevsner. The only railway station mentioned in the first Dorset edition is that (of 1886) at Wareham, where the Dutch gable is called ‘comical’. Recent research has brought to light much about the significance of railway buildings and the role they played in the Victorian age. Today we know the names of the designers of the stations at Sherborne, Gillingham, Maiden Newton, Swanage, Corfe Castle and Dorchester West (another by Brunel) – although we still don’t know who contributed the mirthful gable at Wareham.

So what does the revision of a county like Dorset entail? My method, and probably that used by most revisers, was to tackle the county on a parish-by-parish basis, starting with the East Dorset district and gradually working my way west. Bundles of research material would be gathered, such as extracts from early OS maps, copies of relevant pages from the Royal Commission inventory volumes on Dorset, copies of the statutory lists, as well as any local guidebooks.

The Buttercross, Poundbury, Dorchester

Rarely has a new suburb caused more controversy than Poundbury, built on Duchy of Cornwall land to the west of Dorchester. The architectural profession has generally pooh-poohed its use of traditional styles, and barely noticed the intensive ecological aims that have gone with them. At times the familiar Georgian and Regency styling seems disquieting: something one expects in historic town centres but not as part of new development.

And while the intention is to evoke the traditional building forms of Dorchester, or at least Dorset, nothing of the Victorian or Edwardian age (apart from several Arts and Crafts-looking blocks) is present. So time appears to stand still, at about 1830. It is easy to criticise, but when one considers the alternatives we see just how Poundbury succeeds in its place-making. If popularity among residents is any measure, it also succeeds on that score. The Buttercross by Ben Pentreath (pictured here) forms the centrepiece to an informal square on the southern side of the suburb. Credit: James O Davies/Yale University Press

My first visit (on 25 May 2011) took in Alderholt, Chalbury, Colehill and Corfe Mullen church. Later excursions were far more exhaustive (and exhausting!) in their range of places and buildings. Following each visit, the relevant section of the gazetteer would be given a first re-draft, with buildings or places marked up for further research if necessary.

Since I had covered the country houses in my earlier work (published by Spire Books in 2013 and 2014 as East Dorset Country Houses and West Dorset Country Houses), documentary research was concentrated largely on churches. For the Anglican Diocese of Salisbury, this involved the faculty records on church alterations held at the Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre, conveniently close to my home in Gloucestershire (but not so for those living in Dorset). Otherwise, there were less frequent visits to the Dorset History Centre in Dorchester, and occasionally to what is now the Historic England archive at Swindon.

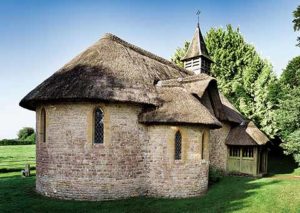

St George, Langham Lane, Gillingham

Down a minor lane near Gillingham is the picturesque thatched church of St George. It was commissioned as a memorial to John Kenneth Manger of Stock Hill House, who was killed in 1915 while fighting at Ypres in Belgium. His parents chose Charles Edwin Ponting of Marlborough as their architect; his projects were generally more grandiose, such as Marlborough Town Hall of 1902, and his best church in the county (St Mary, Dorchester) is much larger. Here, in contrast, all is peaceful Arts and Crafts simplicity, the thatch rolling over the gables and a plain, serene interior. It was built in 1921 but strangely found no mention in the first edition. Credit: James O Davies/Yale University Press

This process was repeated until my final gazetteer-editing visit to the county on 31 January 2017, the last place being the delightful 1857-8 church at Catherston Leweston by J L Pearson (best-known as the architect of Truro Cathedral). Editing and re-editing followed, with further fact-checking. Also, the introductions were largely re-written, something that could not really be attempted until the facts in the gazetteer were fairly well established.

Anyone reading the book today will also notice the expansion of many entries (for example, Victorian and later church furnishings and stained glass are more thoroughly covered) and a number of entirely new entries. Not all are for buildings started after the previous edition went to press; some are older buildings that were omitted last time. Three of these are described in more detail on the panels scattered through this article, as are two new schemes that are of much more than passing interest.

Riviera Hotel, Preston

Art Deco was much derided by architectural historians in the post-war period. It was considered impure, neither truly Modern nor a genuine stylistic revival, such as Neo-Georgian. When the first edition was written in the late 1960s, Art Deco was still under-appreciated. Even in the 1930s, John Betjeman called it the ‘Tel-Aviv’ style; alternatively it was referred to, sniffily, as ‘Moderne’ with an ‘e’. But today such buildings as the great Riviera Hotel at Preston, overlooking Weymouth Bay, are celebrated. Designed by the otherwise obscure L. Stuart Smith (and built in 1937), it has a long, arcaded frontage, behind which the hotel rooms are arranged. In the 1930s a clock tower was de rigueur, and there is one here forming the centrepiece. Today, thinking of seaside resorts, we regard such buildings as an essential part of a British holiday. They are the architecture of sheltered promenades, bandstands and amusement arcades. Credit: James O Davies/Yale University Press

The Buildings of England: Dorset, by Michael Hill, John Newman and Nikolaus Pevsner (ISBN: 978-030022-478-8) will be published on 15 May 2018 at £35 by Yale University Press, http://yalebooks.co.uk