Spiritual twins

Roger Guttridge investigates the uniquely historic roots of the Wimborne-Ochsenfurt town twinning, which marked its 30th anniversary last month

Published in December ’19

MOST TOWN twinnings began as rather artificial arrangements between communities with little in common – products of a post-war boom in entente cordiale, bonhomie and an appetite for continental travel. But the beginnings of Wimborne’s twinning with Ochsenfurt in Germany were very different. Uniquely, these two towns half a continent apart have a genuine and historic spiritual connection that dates back almost 1300 years. And this connection owes its revival to the curiosity of one man.

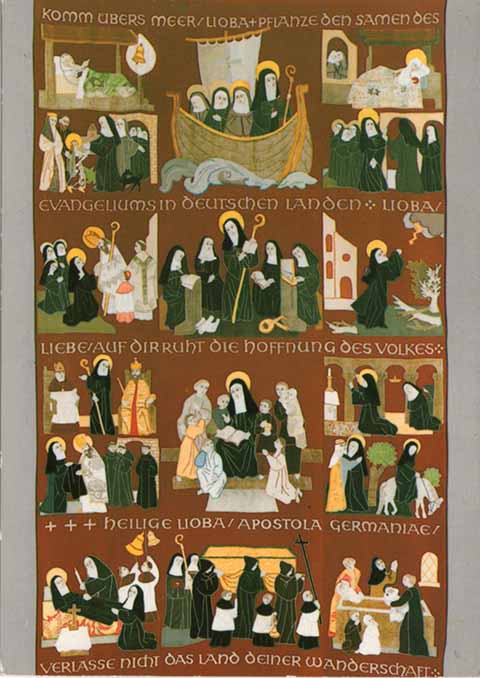

Father Adam Zirkel, Ochsenfurt’s Roman Catholic priest in the 1980s, was investigating his parish’s history and was intrigued by some 8th-century documents concerning an ancient link with Wimborne. He discovered that at some time in the 740s, the Devon-born missionary, St Boniface, wrote to Tetta, the Abbess of Wimborne’s Anglo-Saxon nunnery, asking for help in his efforts to convert the pagan tribes of northern Germany to Christianity. The nunnery – founded by King Ine’s sister, Cuthburga, in about AD 705 – was already famous for its missionary work and Tetta selected 30 of her 500 nuns for the task. They included Boniface’s niece, Leobgytha (which the Germans changed to Lioba), and two other relatives, Walburga and Thecla or Thekla.

Lioba – thought to be the leader of the group that travelled to Germany – was a great admirer of her uncle and corresponded with him in Latin. Some of her letters still survive. In about 750, he made her Abbess of Bischofsheim, from where she founded a number of other monasteries. Walburga, who had spent 28 years at Wimborne before going to Germany, and Thekla both worked under Lioba at Bischofsheim before becoming Abbesses of Heidenheim and Ochsenfurt respectively. St Thekla, who also later became Abbess of nearby Kitzingen, where she died in 790, is remembered today as the patron saint of Ochsenfurt’s Roman Catholic church. Her statue stands in the church alongside those of St Boniface, now patron saint of Europe, and St Lioba.

Armed with all this history, Father Adam booked himself a holiday in Wimborne and made straight for the Minster, where he met the then vicar, Canon Barney Hopkinson. Barney introduced him to Father O’Brien, the priest at St Catherine’s RC Church in Wimborne, who happened to speak German as fluently as his opposite number from Ochsenfurt spoke English. The priestly trio got on famously and their meeting led directly to a visit to Ochsenfurt by a small group from St Catherine’s. This in turn led to a remarkable ‘Celebration of Peace’ in the Minster in 1985 – the 40th anniversary of the end of World War 2.

‘The Archbishop of Canterbury had said that he felt this should be a time of reconciliation rather than a commemoration of victory 40 years earlier, because nobody is a winner in time of war,’ former Mayor of Wimborne Margery Ryan told me some years later. ‘German people were going to be at Westminster [Abbey] and we thought it would be nice if we could get someone from a German town to come over and join us in a reconciliation. The obvious thing was the connection with Ochsenfurt, which had recently been re-established after 1250 years.’

Margery’s husband, Denis, who himself was Mayor of Wimborne in 1985, approached the Burgermeister of Ochsenfurt, Peter Wesselowsky, who changed his plans in order to accept the invitation and brought with him eight teenagers, whose presence symbolised the unity and peace of modern Europe as perceived by the new generation. Six hundred people attended the Celebration of Peace and found it an intensely moving experience. Father O’Brien welcomed the German visitors in their own language and representatives of other Wimborne churches also contributed. Speaking in fluent English, Father Adam then delivered a powerful sermon that was clearly spoken from the heart. ‘You have opened your homes and your hearts to us,’ he said. ‘We would like to take your hand in friendship but we will hold it very gently because we know it still bears the scars of the hurt that we have caused.’

The service included music by the Queen Elizabeth’s School orchestra, whose playing so impressed Herr Wesselowsky that he invited them to give a series of concerts in Ochsenfurt. This was the first of many musical exchanges, which became an annual feature of the twinning arrangement in its early years. Since then there have been exchanges by many other groups including football teams, artists, chess players, Scouts, choirs, musicians and traditional dancers. The twinning body has also helped to facilitate numerous exchanges by individuals and private groups.

Prompted by the spirit of the 1985 peace celebration, civic leaders in both Wimborne and Ochsenfurt began to make plans for a formal twinning arrangement. The date chosen for the ceremony in Ochsenfurt – November 1989 – could hardly have been more auspicious. ‘We were approaching Ochsenfurt when we heard the terrific news that the Berlin Wall had fallen,’ recalled Margery Ryan. ‘There was euphoria and we had the most wonderful twinning ceremony. Hundreds of families were coming over from East Germany. Each town in the west was paired with one in the east and Ochsenfurt was given Colditz.’ Ochsenfurt also brought forward its Armistice Day events by a week to accommodate the British guests. The charter that officially launched the ‘partnerschaft’ or twinning organisation was signed by the two Mayors, Mrs Ryan and Herr Wesselowsky, on 14 November 1989.

To kick off the 30th anniversary celebrations, 23 Wimborne members visited Ochsenfurt in July 2019, when highlights included a presentation by Peter Wesselowsky on the three decades of twinning. At Wimborne, the main event was at Wimborne’s Allendale Centre on 16 November, with the German Consul as guest speaker, followed by a commemorative service in the Minster the following morning.

As well as the anniversary celebrations, the Wimborne-Ochsenfurt Twinning Association also organises regular events throughout each year including joint events with the association that runs Wimborne’s twinning arrangement with Valognes in France. The regular programme includes walks and talks, ‘Kaffe and Kuchen’, skittles, boules matches and wine tastings. A St Nicholas Night dinner is held in December and members have regularly served bratwurst and glühwein from a stall in Wimborne Square during the annual Christmas lights switch-on.

Despite all these events, Philip Maul, chairman of the Wimborne-Ochsenfurt association, admits that maintaining the link is more challenging than it used to be. ‘Twinning arrangements were a post-war concept,’ he says. ‘Younger people don’t feel the need for it. If they want to exchange with people in Germany, they just go. The ease of travel has meant that the twinning concept is not needed as much. The biggest problem is the distance. By contrast, if you wish to go to Valognes, you can hop on a ferry from Poole to Cherbourg and you are at the twin town in half an hour.’

One idea being floated is to bring Wimborne’s two twinning bodies under one umbrella. ‘I think it would be good to look at the Ochsenfurt model, where they have twinning arrangements with Colditz, Wimborne and places in France and Italy, all of which come under the ambit of a single organisation that deals with cultural exchanges,’ says Philip Maul.

No-one who visits Ochsenfurt and its near-neighbour, Marktbreit (famous as the birthplace of Dr Alzheimer, who identified the disease of that name), can fail to notice that both are just as steeped in history as Wimborne. Ochsenfurt’s ‘new’ Town Hall, which overlooks the main square, was built in 1497 while the ‘old’ Town Hall 100 yards away is a century older. The ‘new’ Town Hall also has some mechanical devices to rival the Minster’s astronomical clock and quarterjack. Its famous mechanical clock dates from the 16th century; other moving features include a pair of oxen and a pair of councillors whose faces appear at the windows. On the Town Hall steps, a weather-beaten stone lion reminds visitors that Richard the Lionheart is said to have passed this way at the time of the Crusades. All around are ancient arches, medieval towers and narrow cobbled streets lined by timber-framed buildings, flowers spilling picturesquely from their window-boxes.

Ochsenfurt – population 11,000 – lies 20 kilometres south of the city of Würzburg and sits on either side of the River Main, a navigable tributary of the Rhine and an occasional source of major flood problems. High-water marks on the museum wall indicate that floods have reached depths of up to fourteen feet in the past, although these days huge sliding flood barriers stand ready to plug the gaps in the fortified town walls.

Modern Ochsenfurt boasts one of the world’s biggest sugar beet factories, two large breweries and Kniepp’s natural wellness products factory, while the countless acres of vines on sun-drenched hillsides overlooking the Main valley produce quality Franconian wines. A traditional challenge in Ochsenfurt in past centuries was to drink three litres of wine in one go, the names of those who succeeded (including some women) being recorded in an old book. The Wimborne nuns are not listed, although tradition has it that they took some Dorset vines with them to Germany. Could it be that some of the grapes that provide Ochsenfurt with much of its lifeblood today are descended from plants that 1300 years ago grew on the vine-friendly southern slopes of Colehill, an area still known as The Vineries?

The Wimborne-Ochsenfurt Twinning Association’s website is:

www.wimborneochsenfurt.org.uk