‘A pretty neate town’

Blandford may lack a major author of its own but, as Michael Handy describes, in previous centuries it had a web of writing connections

Published in November ’19

WHEN ONE thinks of Lyme Regis and literature, one thinks of Jane Austen, John Fowles and even obliquely Henry Fielding. For Dorchester it is Barnes and Hardy, for Bournemouth it is Verlaine, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Shelleys. Whilst Blandford Forum doesn’t have these immediate connections, it has been written about by many visitors over the centuries and has been the centre of a district in which much literary work of note was done; it is also the birthplace of probably the most famous war poem in English literature.

Blandford’s position on the road from Exeter to London meant it attracted travellers passing though as well as those visiting the county. Daniel Defoe came to the town in 1724 and described it as ‘a flourishing borough and market town containing 500 houses, many of them built of stone. No town hereabouts has so great a number of gentlemen’s seats round about it as this, invited hither perhaps by the pleasant downs adjoining it, which can hardly be equalled in the world. It is now one of the most considerable towns of the county for travellers.’

There may have been five hundred houses when Defoe visited, but seven years later the town was razed by fire, so not that many of the houses Defoe refers to were in fact stone or, if they were, they were not immune to the conflagration. The town was famously rebuilt by John and William Bastard.

165 years earlier, Thomas Bastard had been born in Blandford. He achieved literary immortality for his Chrestolos. Seuen Bookes of Epigrames. Bastard himself was described as ‘much guilty of the vices belonging to poets’, which one imagines to cover a multitude of sins, and was forced by ‘libelling’ to abandon his Fellowship at Oxford University in 1591. Thanks to friends in high places, he secured a living as a vicar at Bere Regis in January 1593. His literary endeavours did not bring him happiness and described a miserable family life with ‘a wife who was no great help-meet’. According to the journal Athenae, he ‘became towards his latter end, crazed and was put into prison at Allhallows [Dorchester], and in a mean condition, was buried in the churchyard belonging to that parish, leaving behind him many memorials to his wit and drollery.’

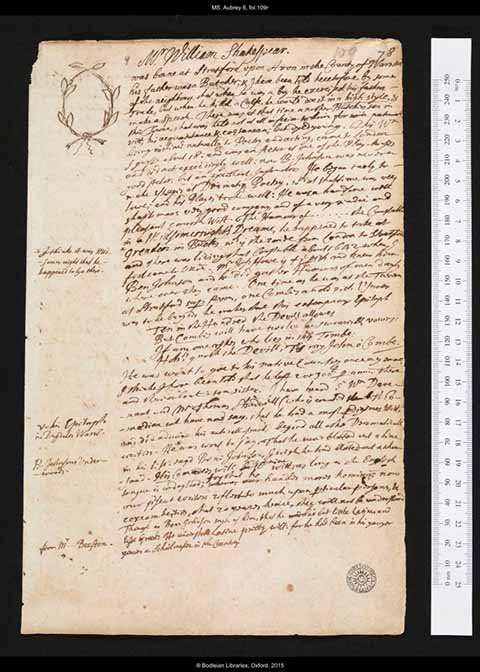

Blandford was home to Blandford Grammar School, where antiquarian and writer John Aubrey completed his schooling. He described the school as ‘the most eminent schoole for the education of gentlemen in the West of England’. He was less complimentary about the town in 1640, describing it thus: ‘At Blandford as much roguery as Newgate.’ Aubrey’s no-nonsense style in despatching the reputation of the town was even more in evidence as the author of Brief Lives, an astonishingly straightforward collective biography. Brief Lives bluntly mocked the lives of eminent figures. For instance, Aubrey wrote of John Milton: ‘His complexion exceeding faire – he was so faire that they called him the Lady of Christ’s College.’

Celia Fiennes, who from 1684 to about 1703 travelled England riding side-saddle, wrote a book of her travels for her personal gratification. It was published 200 years later and contains the following vignette on Blandford: ‘From Wiltshire I went to Blandford in Dorsetshire through a haire waring [a hare warren] and a forest of the kings [Cranborne Chase]. Blandford is a pretty neate town.’

A rather stricter view was taken of the town in a poem by Winterborne Whitechurch-born poet, William Holloway, who is thought to have based his poem ‘The peasant’s fate’ (1802) on the workhouse at East Street opposite what is now Nightingale Court:

‘A hopeless race that own yon bleak abode,

Of Grief and Care, beside the public road,

Propp’d are whose leaning walls, whose hanging door,

Drags heaving on the earthen floor,

Keen through the shatt’d casements cold winds blow,

The half-stripp’d roof admits the swirling snow…

A ragged, meagre, pale, dejected band!

Here is the man who wealthy days have seen,

Here too, the damsel… once the village queen,

Fell a sad victim to Seductions pow’r,…

Here orphans bend to Poverty’s hard laws,

Whose fathers perished in our country’s cause,

Wives, anxious wives! For distant husbands mourn,

In vain anticipation of their return.’

According to the census of 1851, one of the two hundred residents of that same workhouse was a 25-year-old blind woman called Caroline Watts. She would later have a book of poems published – Poems by a Blind Girl – in 1864 by Petter and Galpin, which would become the publisher Cassells in later years.

Blandford’s Thomas Creech was a teacher and translator of note. His 1682 translation of the Roman poet, Lucretius, into verse was warmly praised by John Dryden, when Dryden published his own translations from Theocritus, Lucretius and Horace. Creech was headmaster of Sherborne School for two years. In his later years he moved to Oxford, where he fell in love with and proposed to Miss Philadelphia Playdell, whose friends blocked the union. Creech took his own life and left half his money to his sister, Bridget, who had married Thomas Bastard of Blandford: not the epigrammatist, but the architect father of John and William. One of the many scandal penny sheets of the day sensationalised the suicide in a pamphlet called A Step to Oxford, or a Mad Essay on the Reverend Thos Creech’s hanging himself (as ’tis said) for love. With the Character of his Mistress.

Creech wasn’t the only classicist translating works for publication. Christopher Pitt, born in Blandford in 1699 to Dr Christopher Pitt (who himself had contributed a translation of Lucretius’s description of the plague of Athens to Creech’s publication) was best known in literary terms for his essay on Virgil’s Aeneid, which grew to become a two-volume translation of the whole poem. While its academic rigour was widely praised, his prose style was perhaps less so. Samuel Johnson, in comparing Dryden’s translation with Pitt’s, said: ‘Dryden’s faults are forgotten in the hurry of delight, and Pitt’s beauties are forgotten in the language of a cold and listless perusal. Pitt pleases the critics, Dryden the people. Pitt is quoted, and Dryden read.’ Ouch!

While Pitt’s prose style may not have won admirers, his personal demeanour was something else. After his death in 1748, of the Pitts’ recurring malady of gout, tributes noted that he died without a single enemy, while the memorial tablet in the church at Blandford referred to ‘the universal candour of his mind and the primitive simplicity of his manner’. His brother, Robert, translated the first five books of Milton’s Paradise Lost into Latin verse.

For some reason, Blandford seems to have been blessed with more than its fair share of writers on religious matters: Rev. Richard Derby, Rev. William England (son of the Venerable William England, Archdeacon of Dorset), George Buchanan Day, Rev. Arthur Malortie Hoare (son of the Venerable Charles James Hoare), Rev. William Sherley, author of The Episcopal Government, and William Wake, later Archbishop of Canterbury, who wrote The State of the Clergy… historically deduced.

Blandford has also produced some noted legal authors, probably principal amongst whom is Sir Thomas Ryves, whose family name will be forever associated with the almshouse in Salisbury Street. The eighth son of John Ryves of Damory Court, Thomas was one of a number of lawyers in the family (his brother, William, was Attorney General of Ireland) and Thomas specialised first in ecclesiastical law, then later in Admiralty law, becoming judge of the Cinque Ports. He fought – apparently ably and enthusiastically – for the King in the Civil War, even though he was in his sixties by the end of the war. He wrote widely on a number of topics including naval history, but also ecclesiastical politics in the shape of his treatise demanding tithes for Irish clergymen to make a living (The Poor Vicar’s Plea of 1620).

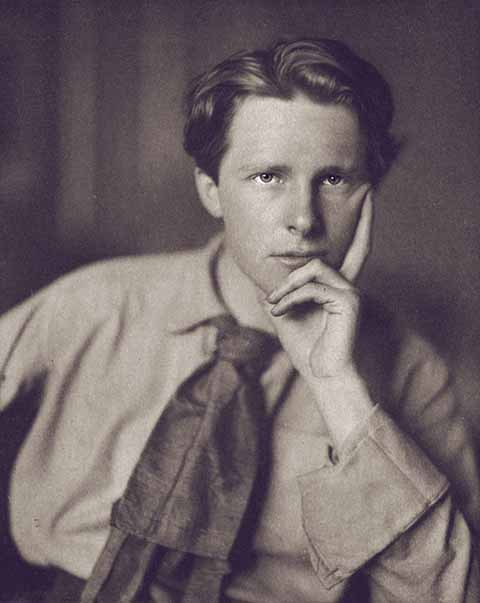

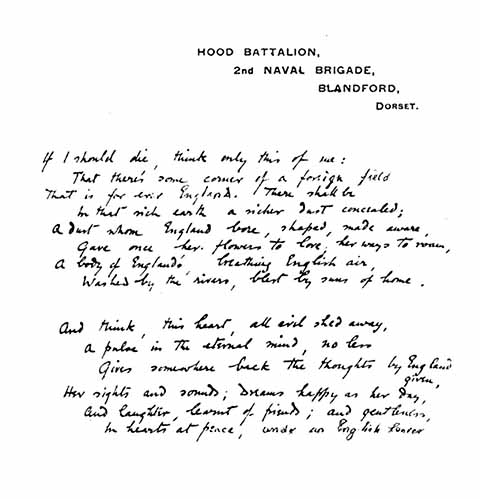

Blandford was a way station for travellers in all stations in life. The most famous words of all penned in Blandford were by Rupert Brooke, while he was stationed with Hood Battalion of the 2nd Naval Brigade of the Royal Naval Division at Blandford Camp in 1915. As he pondered what lay ahead, he wrote the sonnet now known as ‘The Soldier’:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam;

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Brooke’s death was far from poetic. He died of blood poisoning after getting an insect bite before he had even reached the theatre of war; he was buried in an olive grove on Skyros.

Finally, the author of Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon, visited Blandford in 1760 as a 23-year-old Hampshire Militia captain: ‘Our stay at Blandford was very agreeable, the weather fine. The gentlemen of the county showed us great hospitality, particularly Messrs Portman, Pleydell, Bower, Sturt, Brain, Jennings, Drax and Trenchard, but partly through their fault, and partly thro’ ours, their hospitality was often debauch.’