The Broadstone collision

Joël Lacey sifts through the archives to tell the tale of a journey that ended in tragedy

Published in October ’19

Just before Christmas 1890, Edith Lowe, who had recently moved down to Poole, was looking forward to the visit of two friends from Birmingham. The two sisters – Sarah and Elizabeth Worthington – travelled from Birmingham to near Bristol, then caught a connecting service to Bath, where the ultimately Bournemouth-bound coaches were hitched to a Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway engine for the final part of the journey. Only Sarah would arrive.

On the afternoon of 23 December 1890, after the sun had gone down, a light engine and tender at Broadstone Junction was being driven by William Charles Squires, assisted by his fireman, Albert John Stone. Looking along the line, Squires saw that there was no danger signal on the main line and crept along at low speed.

In the signal box by the junction, was a carpenter, George Clark, who had popped in to ask the signalman, Walter Gosney, about travelling on to Wareham.

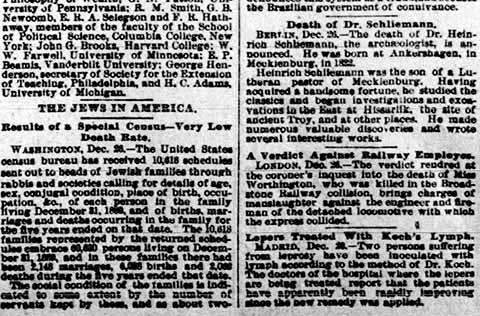

Above The outcome of the inquest of Elizabeth Worthington was reported as far afield as the United States, as seen from this front page report from the Baltimore Sun

At the Board of Trade enquiry, held just four days later, the sequence of events was laid out as follows: ‘The 2.15 pm train from Bath to Bournemouth West, when entering Broadstone Junction station at 5.22 pm, one hour and ten minutes late, came violently into collision with the London and South-Western light engine and tender No. 290, which had arrived from Wimborne on its way to Bournemouth at about 5.20 pm, and which, having been stopped at the down main line home-signal for one or two minutes, had run forward when the junction and other signals were taken off for the Bath train.

‘The consequences of the collision were disastrous. The trailing wheels of the tender of the light engine were knocked from under it, but the engine, upon which steam had been applied, ran forward for a distance of 279 yards. The engine of the Bath train left the rails, and after running for 54 yards with the loose wheels of the tender of the light engine in front of it, came to a stand slewed across both lines of rails of the Poole and Bournemouth branch line.’

Inside the train, amongst a host of injured passengers, Elizabeth Worthington lay dead. According to the Dorset County Chronicle of 1 January 1891: ‘She died instantly, her head completely battered in,’ when she shot out of her seat at the moment of impact. She was the only fatality, but her sister suffered a broken leg, hand and facial injuries.

On 2 January, an inquest into the causes of Elizabeth’s death was opened by the Wimborne coroner, Mr H Chislett. The body of the deceased having been identified, he heard evidence from Clark and Gosney. Signalman Gosney deposed that at 5.14 pm he received the departure of the Bath train from Bailey Gate Station. At 5.15 he received a departure signal that a light engine had left Wimborne Junction. He kept all his signals at ‘danger’ until the light engine arrived at the stop signal outside the station. Before that he put his road right for the Somerset & Dorset train. As soon as he saw that the light engine was stopped dead at the stop signal, he took off his signals for the Somerset & Dorset train going into the station.

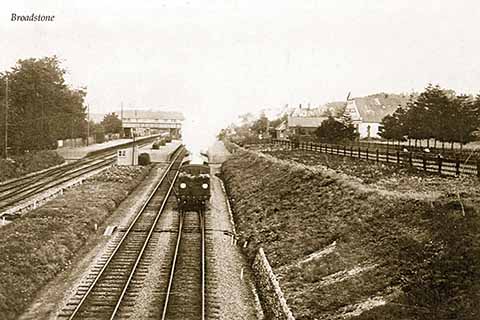

Broadstone at the time of the accident was a largely rural area bisected by the railway lines at Broadstone Junction

After the signals were all off, the engine was still standing at the stop signal. He went and made an entry of the arrival of the light engine at the stop signal in a book kept for that purpose. When he looked again, to his horror he saw the light engine creeping past the stop signal, which was still up and at danger. He called out, ‘Where are you coming to?’ He received no answer and it did not stop. He then left his box and ran along the line towards it, and said, ‘Why don’t you stop? You must be mad.’

Still he received no reply, and the engine went on. He then ran back to his box and threw all the signals at danger. The light engine passed by his box and stopped between it and the station. He then saw that there were no tail lights on it. The accident then happened. He had never seen the light engine without tail lights before. He had never known the engine pass a stop signal in that way before, when it was against it. He had not time to stop the Somerset & Dorset train, and it could not pull up when he set all the signals at danger.

Squires, the driver of the light engine, after being cautioned by the coroner, said he left Wimborne at 5.14 on that Tuesday afternoon, and proceeded as far as Broadstone Junction stop signal, which was at danger. The fireman got off to see if the head light was right, and on his getting on the engine again witness saw the stop signal and the junction platform signal taken off, which authorised him to proceed. As he passed the signal box, he heard the signalman call out, ‘Where are you going now?’ He went a few more yards past the signal box, when the fireman said: ‘Look out, mate, the Somerset train is close on us.’ He turned on steam, but the Somerset engine struck the tender of his engine and he was knocked back into the tender. On getting out, he shut off steam and stopped, and then found his tender smashed and a pair of wheels knocked off. It was owing to his having steam on that his engine went so far after being struck. He had been an engine driver for eighteen months, and had passed the junction daily since March. He and his mate were perfectly sober.

Several other witnesses having been called, the coroner summed up, and the jury returned a verdict of manslaughter against the driver and fireman of the light engine and exonerated the signalman from blame.

On 10 January 1891, Squires and Stone were brought up on remand at the Wimborne Police Court, charged with having by culpable negligence caused the death of Elizabeth Worthington, aged 33, at Broadstone Junction, on 23 December 1890.

Appearing as a witness for the prosecution, George Clark, the Wareham-bound carpenter, said he ‘saw the light engine standing at the stop signal, and directly the signalman drew off his signal for the Somerset train to come across, the light engine moved on from the stop signal towards the signal box…. The signalman ran out and shouted…. The Bath train ran in immediately, and smashed up in collision with the light engine.’

Clark saw the Bath train come through the cutting; the light engine was then drawing away from the stop signal. He went at once to the train and helped to cut out the passengers, finding one lady dead, and he assisted in removing the body.

The defence then pointed out that as Stone was only following his driver’s instructions on all points, he could not be held responsible. And, as regarded the driver, it was impossible that any jury would ever convict, for it was solely a question between the signalman and him – whether the former had not forgotten something. The defendants by what they did were rushing to certain danger to themselves, but on the other hand the signalman had admitted breaking the rules (by having Clark in the box) and had to justify his position. Although he put his road right for the Bath train, it was quite possible he had just before made some little involuntary mistake by which the light engine was asked to proceed.

The Bench, after half an hour’s consultation in private, discharged the fireman, but committed Squires for manslaughter.

In Dorchester’s Crown Court, at the Dorset Assizes, Lord Chief Justice Coleridge was sitting and he gave extensive instructions to the grand jury about the nature of neglect, culpable homicide and manslaughter. Despite the former’s discharge by the Police Court, both Brown and Squires were indicted for ‘feloniously killing Miss Elizabeth Worthington’ on the strength of the coroner’s verdict. When, however, the case came to be judged, the prosecution (which was conducted on behalf of the Treasury, before the invention of the Crown Prosecution Service) offered no evidence against the fireman, Albert Stone and he was formally discharged.

Between the Police Court case and that of the Assizes, the Treasury official in charge of the case was overwhelmed with work, with devastating consequences to the later trial. When it came to instructing the jury about the case against Squires, the presiding judge vilified the Treasury, for whom the key prosecution witness, who should have given evidence as to the legal identification of the victim, was absent. In the absence of proof of a victim’s identity, there was, according to the Lord Chief Justice, no proof of a crime and so the jury’s duty was to acquit William Squires.

In accordance with the judge’s instructions, the jury returned a formal verdict of not guilty for want of proof. According to the County Chronicle’s report: ‘At this announcement there were demonstrations of satisfaction in court, but these his Lordship quickly repressed.’