Fun of the fair

Roger Guttridge recalls Shroton Fair, a highlight of Dorset’s social calendar

Published in October ’19

There’s an old Dorset saying that blackberries should never be picked ‘after Shroton Fair’. So says my friend, Barry Cuff. ‘My father told me this was because the devil had spat on them,’ adds Barry, an enthusiast for all things Dorset.

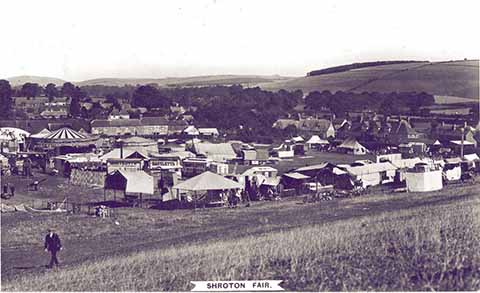

The annual fair at Shroton, aka Iwerne Courtney, was one of the oldest in England, founded more than 700 years ago and traditionally held on 24, 25 and 26 September, by which time blackberries are probably past their pick-by date. It may once have been a week or two earlier, as Hutchins’ History of Dorset tells us that a fair was held under Arnold’s Hill on Holyrood Day – 14 September.

Shroton Fair was a great social and commercial event that attracted thousands to the fields under Hambledon Hill. It was known for its cattle, sheep, horses and dairy produce and for hiring labour. In later decades it included a funfair and one year a menagerie whose star attraction was a tiger.

In 2009, Shroton-born Michael Dibben told me: ‘For a small child in a quiet village, life didn’t get much more exciting than when Cole’s Funfair began arriving on the Sunday morning. Owner Bernard Cole insisted that the dodgems were up in time for church Evensong on the track. The Methodists held an open-air service in the afternoon. The Portman Hunt also met in the Fair Field and we had the day off school.’

In 2009, Shroton-born Michael Dibben told me: ‘For a small child in a quiet village, life didn’t get much more exciting than when Cole’s Funfair began arriving on the Sunday morning. Owner Bernard Cole insisted that the dodgems were up in time for church Evensong on the track. The Methodists held an open-air service in the afternoon. The Portman Hunt also met in the Fair Field and we had the day off school.’

In 1961 Shroton celebrated the 700th anniversary of the village’s fair charter of 1261. ‘Southern Television were present when the hunt met and there was a large fireworks display,’ said Michael. ‘The crowds were the largest I could recall.’

After that, attendances dwindled until the Great Dorset Steam Fair, launched at nearby Stourpaine Bushes in 1969, drove the final nail into Shroton Fair’s coffin. Disgruntled gypsies are said to have cursed the Steam Fair, causing the torrential rain and mudbaths for which it became famous. Not that Shroton was immune to the weather. ‘There were years when it rained and the large fair vehicles got stuck in the field,’ Michael added, ‘but I remember my mother referring to “Shroton Fair weather”, which meant misty mornings that evolved into warm and pleasant autumn days.’

In 2011, I visited 91-year-old Betty Hunt (née Elliott) in a Shaftesbury nursing home to hear her Shroton Fair memories. ‘All sorts of mischief went on there – but not destructive,’ she assured me. ‘We used to walk up there, pay to go in and meet people, including boyfriends.’ Betty, who lived at Ranston Farm, remembered ‘great piles of brandy snaps’, a shooting gallery with balls balanced on jets of water and a Shroton character called ‘Old Gaisford’, who rode to the hunt meet on a donkey. ‘He was bow-legged and lived on his wits,’ Betty told me.

Victorian Dorset’s two literary greats mentioned Shroton Fair in their writings. Thomas Hardy wrote of seeing a woman ‘beheaded’ in a sideshow. In his dialect poem, ‘Shrodon Feair’, William Barnes wrote of the excitement of two young ladies as they rushed upstairs

‘…To shift their things, as wild as heares [hares];

An’ pull’d out each o’m from her box.

Their snow-white leace and newest frocks,

An’ put their bonnets, a-lined

Wi’ blue, an’ sashes tied behind…’

In Down Dorset Way (1954), Olive Knott tells an amusing tale of a young man who takes his village’s ‘prettiest maid’ to the fair in his ‘wold donkey-cart’:

‘I were a smartish lad wi’ me collar and tie, and the maidens did look saucy at me, but I ’ad eyes for none but pretty Fanny Day,’ says our hero, Ambrose. His heart thudded as he helped her into the cart and sat beside her. She ‘looked a picture’ in her flowery cotton gown, her ‘comely face a-smilin’’. Ambrose would not have changed places ‘wi’ the King on his throne’.

‘What shall us do fust?’ asked Ambrose as they arrived. ‘There’s roundabouts, swings, shootin’ galleries, switchbacks, hooplas, fortune-tellers, conjurers!’ Fanny chose roundabouts. ‘Up an’ down an’ round an’ round we went; my hoss were close beside ’ers, and when she were up, I were down,’ said Ambrose. ‘Ah! I thought t’ myself. Before Shroton Fair be over, I be a’gwine t’ ax she t’ be my wife. But when we were down agen and strollin’ about, I didn’t know how t’ make a start.’

The day wore on but still Ambrose could not find the words he sought. As darkness fell and they prepared to leave, he stammered: ‘Shroton Fair ’ave come and Shroton Fair ’ave gone. I’ve won dree coconuts, a clock, a couple o’ vases but there were zummit else I wanted to win.’

‘Ambrose, don’t be greedy,’ said Fanny. Thinking he’d been misunderstood, Ambrose slipped his arm around her waist. But before he could make his intention plain, the cart lurched and pitched them onto the verge.

‘Never mind, Ambrose,’ Fanny chuckled. ‘I won my bet.’ Her suitor shot a puzzled look. ‘Someone laid a wager that I wouldn’t ride to Shroton Fair in a donkey-cart.’

Ambrose never did pop his question, and vowed to fight shy of ‘wimmin’ in the future. And whenever a friend complained about the way their wife treated them, he replied: ‘You axed ’er, didn’t ’ee? ’Twere my wold donkey that stopped I from bein’ in the zame boat.’