From tragedy to transcendence

Jess Thompson tells the extraordinary tale of Raynor Winn and her best-selling book, The Salt Path

Published in October ’19

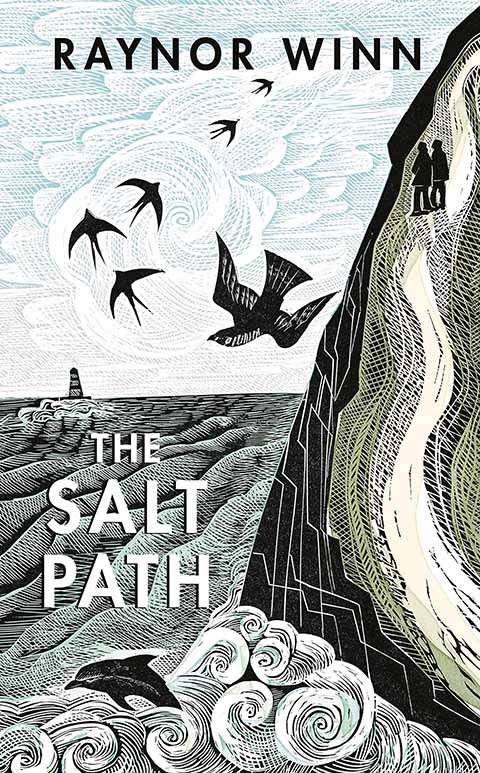

‘It was a beautiful blue, sunny day on the Dorset coast, and we could see right out to the Isle of Wight,’ Raynor Winn says, hesitant at first, then relaxing as the memory unfolds. ‘I remember it was really busy, but there was the smell of the gorse on the cliff-top and you could see those stunning white rocks and the swallows just coming up the cliff face and over your head. And’ – her smile grows wider – ‘it was so exhilarating just to be back on the path.’

She is talking about the moment she and her husband, Moth, returned to complete the 630 miles of the South West Coast Path, re-starting their journey from the opposite direction, near Old Harry Rocks. They had begun the previous August, having found themselves broke and homeless after a business deal went drastically wrong. Then, in the same cataclysmic week, Moth was diagnosed with a rare brain disease and given just two years to live. Two months later they set off, and – although the physicality of walking proved a literal life-saver – when the nights became too cold for wild camping, they reluctantly decided to spend the winter in a friend’s shed.

‘Just being stationary in one place meant that Moth’s health deteriorated quickly, to the point where he was in a worse state than he’d been when we started the walk ….’ Raynor pauses, reflecting on those difficult months. ‘So to find ourselves back on the coast, it was almost like: “This is back where we belong.”’

I ask her which part of Dorset was her favourite and she finds it hard to answer. ‘There were so many. Obviously, those white cliffs, walking up Flower’s Barrow, when you see them in both directions. Or the incredible sense of peace you feel at the Fleet Lagoon behind Chesil Beach. Walking along there on a perfectly still hot summer’s day was the most tranquil thing I’ve ever done.’

I wonder if the experience made her more spiritual? ‘No,’ she answers bluntly, ‘but it did perhaps give me a more spiritual connection to the natural environment.’ Later she reflects further: ‘We started out so anxious and desperate, in such a state of fear about what the future would hold. But as we walked, it changed. Just putting one foot in front of another, taking the next step, and the next.’ Now her voice – soft, with hints of a Staffordshire accent threading through it – changes to that of a storyteller. ‘And that became the reason to go on: just to pass through that strip of wilderness. Because we’d stopped worrying about what would come next, and the act of walking became almost like a meditation. So, if you’re going to talk spiritual, that would be it.’

One of the most memorable parts of her book recalls members of a forest community inviting them to spend the night somewhere near Weymouth. When I ask her if, ten years previously, she could have imagined herself in that situation, I suddenly get a terribly British ‘I wouldn’t have dreamt of it.’ But then, once the laughter subsides, she talks about homelessness in a way that shows her passion. ‘When you’re there, you find that we’re all the same, that we’re all just getting by, just finding a way. You have so many preconceptions about what makes a person homeless, but really everyone has their own story.’

This particular story of Dorset kindness is also one of rural poverty. ‘There are people who can’t afford to live where they work because they’re often working seasonally, with zero hours contracts – things that landlords aren’t happy to accept as income.’ I ask if she worried about exposing the camp. ‘Yes, of course. So whenever I write about people who are living in this way, I move their localities to protect their survival.’

Did she and Moth experience many genuine acts of kindness, I wonder. Again, she pauses. ‘We experienced kindness from the most unexpected places, usually from people who had the least to give. That was probably one of the most uplifting things: to see how generosity of spirit really does exist among people who have nothing.’

And people who have a lot? I ask – conscious of pockets of huge wealth along the coastline. ‘I think there were many opportunities where people could have offered us help but didn’t,’ she says, before immediately turning it into a positive. ‘It amuses me that the people who attend my talks, lovely people all of them, maybe had they encountered me in a previous incarnation they might … not have treated me in the same way? But hopefully it’s a good thing that I get to talk so much, and maybe next time they meet someone who looks like I did, they’ll be different.’

For people who have read her book, the burning question you have at the end of what is essentially a love story is how Moth is today. In person he’s a sprig of warm vitality: the brightest blue eyes beneath stark white hair. And, just like they planned five years ago, he has since completed a degree at the Eden Project. When I ask if he is working, Raynor becomes mysterious: ‘He’s doing something, all of which will be revealed in my follow-up book.’

The other question she is often asked is whether she would do it all again. ‘Absolutely,’ she says. ‘No hesitation. Without losing the house, I don’t think we’d have discovered how walking would help Moth’s health. Because we’d been told there was absolutely nothing that could be done, apart from maybe a bit of physio to keep him moving for a little longer. We’d never have discovered there was a way that we could stall it, delay it. And so I wouldn’t change anything, because it’s all been worth so much more than still having our home. On the path we were happy in so many ways, because we were together, spending all day, every day, just walking. That’s what it gave us: time together in that wild environment. We were so lucky.’