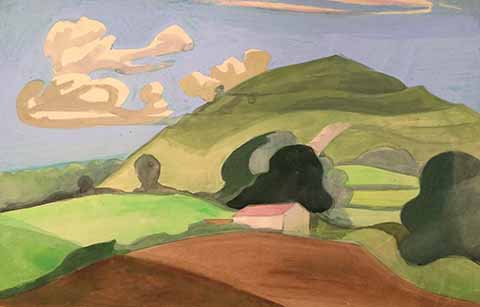

Landscapes of the artist as a young man

Artist David Gommon first came to Dorset in the early 1930s. Fifty years on, he wrote this memoir of that time.

Published in September ’19

I saw Chesil Beach for the first time on a grey winter afternoon in December. I climbed slowly out of Langton Herring to the top of a very steep rise. Suddenly I was confronted, overwhelmed, by the revelation of beach, sea, sky. It was biblical in its splendour and that vivid first sight is with me to this day, more than fifty years later. I can still hear its silence, broken only by the faraway sound of the sea.

I had become friendly with a fellow-student from Dorset at the London art school where I had started as a student when I was sixteen. His father, a retired sailor, lived in an old coastguard cottage down near the sea at Deadman’s Bay. My friend and I agreed to raise some money to buy ourselves a wooden hut, to live and paint there. Van Gogh and Gaugin were our heroes, so we wanted to live rough. As we had little money, this was not difficult. In 1931, it was possible to live on a pittance.

Our hut had the minimum of necessities, including a small battery wireless. A vivid memory is of lying on my camp bed at night, listening to Chekov’s Uncle Vanya. It was a windy night and the hut swayed and lurched, rose from the ground, squeaked and returned to the earth with a shudder. Then the rain started, its sound intensified on our wooden roof, but the voice from the radio continued: ‘And you and I, uncle, dear uncle Vanya, shall see a life that is bright, lovely, beautiful. We shall rejoice.’

One of the strangest meetings I had in Dorset while looking for somewhere to live after the hut was in Iwerne Minster. I had been staying there for several nights and the new owner of the village Post Office had found out in conversation that I was an artist. He asked if I would paint the newly white front of his shop with the words ‘POST OFFICE’ and his name, and this I enjoyed doing. During my lunch break, I went down to the village pub for some bread and cheese and beer. As soon as I pushed open the door, I was aware of a voice reciting, and it was poetry I knew; it was Omar Khayyam:

‘A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness—

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!’

Now, it was not a common practice to recite poetry in country pubs in the 1930s. The reciter was a very upright, military-looking man. I noticed the polished shoes and the army beret worn at a very jaunty angle, the Woodbine cigarettes and the cough. The bar was not very full and we were soon in conversation. It was rewarding for him to find that someone knew the poetry he was reciting.

After much conversation, more Omar and more drink, he invited me to go and live in his home. He had a spare room I could have. He himself lived in a hut at the bottom of a very long garden, while his wife and three children lived in the cottage. He had tuberculosis and the only way he could cope with the disease was to live out of doors as much as possible. The cottage stood on the slope of a hill and had splendid views to the south and west. To the south lay the long range of the Dorset heights from Bulbarrow away westward to High Stoy, right across the whole area of the Blackmore Vale.

I lived up on the slope of that hill all summer; I painted landscapes and pub interiors, drew plants and insects, collected several hundred wild flowers, roamed the countryside as far away as the Cerne Giant and Maiden Castle, read Plato’s Republic, Rousseau’s Confessions, Darwin and much poetry.

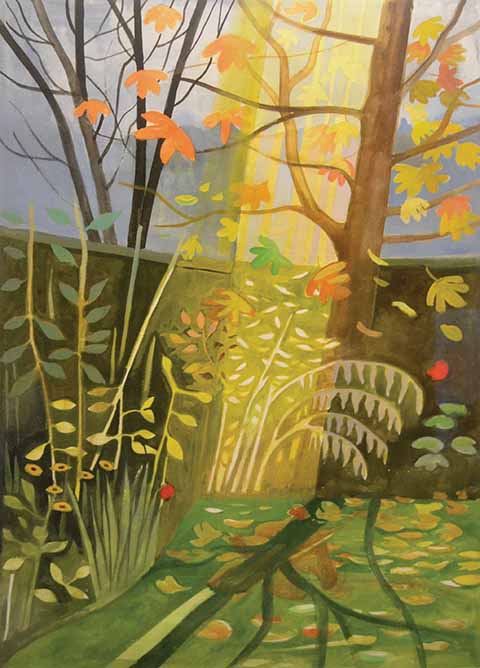

Edge of the wood, 1969, oil on board. This image is not of a particular Dorset location, but contains cues of Hambledon and Portland.

In the evening I went out with my new friend; we cycled to some of the villages he knew and called in for the occasional drink. Our favourite village was Child Okeford, just below Hambledon Hill, which we would climb and, having walked round its ditches, we would then come down to the pub, the Baker’s Arms. It had a visually interesting group of regulars who played skittles, shove ha’penny or cribbage. Although closing time was ten o’clock, some of these activities carried on until midnight, so when we left, we usually pushed our cycles until we were safely distanced from the Baker’s Arms and the village policeman.

This was often the most delightful part of the day, sometimes with moonlight or mist, but always with such a range of scents, especially if the hay meadow had been cut or the honeysuckle was flowering. And then there were all the variety of sounds: foxes badgers, sheep, cattle, owls. I still have, even fifty years later, a large reservoir of images and sounds from that period – still as vivid as ever – and I remember the words of the philosopher Martin Buber: ‘This is the eternal source of art. A man is faced by a form which desires to be made through him into a work.’

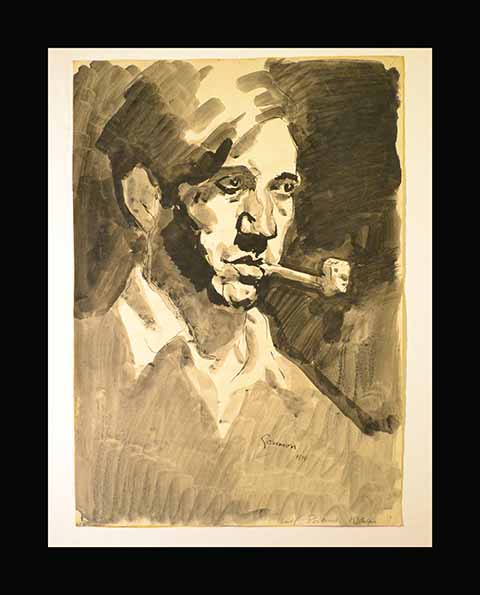

David Gommon (12 December 1913-20 January 1987), was born in Battersea. As a child he saw a Zeppelin shot down, falling out of the sky and burning with the light of the sun. At sixteen, he was enrolled in Battersea Polytechnic and Clapham Art School. During the 1930s he discovered Dorset, which opened his eyes to a particular and ancient landscape that he explored and to which returned in his paintings throughout his life. He was (along with Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland) offered a commission to create posters for Shell Mex, but to his eternal regret he declined, thinking that as an artist, posters and commercial art were ‘not for me’ – a decision he related with the comment, ‘Oh! The stupidity of youth!’

He made friends in the theatre world and sketched a very young Margot Fonteyn and the corps de ballet at Sadlers Wells. After World War 2, he went into teaching art, first at a school based in a castle in Kent, then for 30 years at Northampton Grammar School. He continued to paint all his life.

Art critic Ian Mayes described Gommon’s work thus: ‘I know of few artists whose work communicates such a sense of joy in life as that which comes from these beautifully quiet, very modest and English paintings, so accurate in their evocation of the changing moods and feeling of nature.’

• The Art Stable, nestling beneath Gommon’s beloved Hambledon Hill, has an exhibition of his work from 7 September to 5 October.

www.artstable.co.uk