Smugglers, Dorset and Robespierre

Roger Guttridge examines the unlikely connection between the illicit importation of brandy and the architect of France’s revolutionary Reign of Terror

Published in November ’18

As a young girl in the 1950s, Jane Barrett was fascinated by her maternal grandfather’s romantic tales of yesteryear. Although the family lived at Yeovil, Percy Barrett (1883-1958) originally hailed from Bridport, where he began his career as a picture-framer and watercolour painter before moving to the Somerset town before World War 1. ‘He always maintained that he had some smugglers in his past,’ says Jane. ‘He said their name was Angel, they worked from the Bridport-West Bay area and they smuggled brandy from France.’

So far so good. French brandy was the most commonly smuggled cargo in the 18th and early 19th centuries and there were few near the Dorset coast who were not implicated one way or another. As noted in my book Dorset Smugglers, an Abbotsbury fisherman called Henry Angell served six months in Dorchester Jail in 1841 for smuggling. Without further research, we can’t be sure whether Henry was connected with Percy’s family but, as with most other trades, smuggling tended to run in families.

Telling me her grandfather’s story recently after listening to my talk on smuggling, Jane added that there was one other Percy Barrett tale that stuck in her mind. ‘He told me the smugglers knew and were friendly with Robespierre,’ she said. ‘I believed it when I was younger but as I grew up and trained as a history teacher, I began to doubt it. How could a smuggler from Dorset possibly have known one of the major figures of the French Revolution?’

Whether Percy’s Angel ancestor really was acquainted with one of the most famous revolutionaries in history we will probably never know. But it does seem a remarkably random claim to make – a statement so unlikely that it probably has an element of truth. And suggestions of a link between Dorset’s smugglers and revolutionary France are not as preposterous as some might imagine.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, smuggling was at its height and illicit trading links were well established. Along the Dorset and adjoining coasts, hundreds of thousands of gallons of French brandy were coming ashore illegally every year and supplying not just local markets but much of the country. It has also long been known that during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, smugglers provided a ready-made highway for information of various kinds, including messages from spies on both sides of the Channel. Various French regimes actively encouraged the smugglers, whose work brought British money into their economy and undermined the UK revenue. Napoleon even built accommodation for them at Gravelines.

Isaac Gulliver, the most successful of all Dorset’s smugglers, was known to his French friends as ‘Le Contrebandier’. Gulliver’s descendant, Beresford Leavens of Gillingham, believes his ancestor’s ships carried not only messages but French aristocrats trying to escape the guillotine or the later attentions of Napoleon. Gulliver’s passengers apparently included Francois-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand, who came from St Malo, a port that did good business with the smugglers; the Duc d’Orleans, a member of Robespierre’s Jacobin Club, who went on to live at Priory House, Christchurch, during part of his 21-year exile before becoming King Louis Philippe I of France in 1830; and Louis, Marquis de Fontains and his journalist friend, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Suard, who was harassed by both the Revolutionaries and Napoleon. These were among the richest people in France and their fees presumably contributed to Gulliver’s mounting fortune. When the ‘King of the Smugglers’ died at Wimborne in 1822, his estate was worth £60,000 and included property across four counties.

Of course, all this falls well short of proving a connection between Percy Barrett’s forebear and one of the architects of the Reign of Terror, who presumably had other things on his mind until his own terminal encounter with Madame Guillotine in 1794. But amid the turbulence of those times, who knows? Gulliver’s empire certainly included Bridport and Lyme Regis, where just twelve years after his death the Lyme historian George Roberts wrote that the smuggler kept ‘forty or fifty men constantly employed’ and ‘employed lawyers to arrange his affairs’. Many of Gulliver’s hundreds of workers regularly sailed to France and the Channel Islands before, during and after the Revolution.

There is another intriguing connection. According to Beresford Leavens’s recently revised and reprinted book, Isaac Gulliver: Smuggler, Captain John Harvey from Bedfordshire employed his Bourne Heath cousins, Benjamin Harvey and William Harris, to help the Duc d’Orleans to snatch the French Crown Jewels from Paris. The story goes that in 1792, the Harveys and Harris hired a troupe of circus clowns and acrobats to stage a daring raid on the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne. While the clowns distracted the crowds outside, the acrobats used their skills to break in and steal the jewels, which accompanied the Duc d’Orleans to Dorset on Gulliver’s ship, the Marianne. The jewels included the world-famous Hope Diamond or ‘French Blue’, now worth an estimated $250 million. According to Harvey and Harris descendant and present-day Bournemouth resident, Lord Peter Hamilton-Harvey, three or four chests of jewels disappeared and have never been seen since. ‘They may have been buried or hidden somewhere and would now be worth £3bn,’ he says.

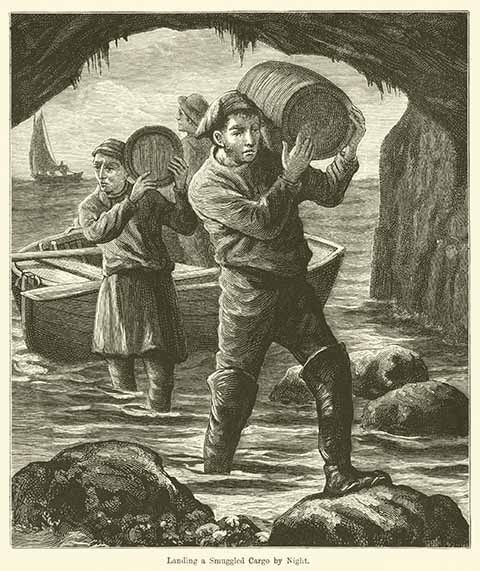

Bringing brandy ashore at night for stowage in a cave to avoid the customs men

Credit: Look And Learn

Lord Hamilton-Harvey adds that Benjamin Harvey lived at Muckleshell on the edge of Bourne Heath and Harris at Bourne House, which stood where Debenhams is today. In the 18th century, it was the only house in what is now central Bournemouth and appears on maps dated 1759 and 1791. It was built by William’s father, William Arundel Harris, many years earlier. Father and son later dug the original decoy pond on the site now occupied by the tennis courts in Bournemouth’s Upper Gardens.

Could William junior be the same William Harris that I wrote about in Dorset Smugglers in 1983? Reading the records of Poole Customs House in the National Archives, I found Harris mentioned several times in connection with smuggling on Bourne Heath. In 1767 he was living at Parkstone but when arrested five years later, he was based at the Decoy Pond House, which was ‘notorious as a house frequented by smugglers’. In 1774 he told magistrates he was ‘born at a place called the Decoy Pond’ and ran away to sea after abandoning his apprenticeship with a Poole shipwright.

The Poole Customs records also tell us that in 1762 smugglers used the Decoy Pond House as a temporary prison for suspected informer Joseph Manuel after kidnapping him from his home at Iford. They then shipped him to the Channel Islands and abandoned him on Alderney ‘with severe injuries’. From maps and other documents, it’s clear that Bourne House and the Decoy Pond House were one and the same, just as the two William Harrises were one and the same.

By this time Gulliver’s business was flourishing: in 1770 the Collector of Customs noted that ‘Isaac Gulliver, William Beale and Roger Ridout run great quantities of goods on our North Shore’ – the beach from Sandbanks to Hengistbury Head. Ridout, from Okeford Fitzpaine, was my own ancestor. Beale was one of Isaac’s in-laws. Gulliver and Harris undoubtedly knew each other even then – and Isaac later made the Bourne Heath village of Kinson his headquarters. Also described in the Customs records in the 1770s is Edward Beake, a ‘very great smuggler’, who happened to be married to William Harris’s sister, Elizabeth.

And then there is the story that the Duc d’Orleans escaped from France disguised as William Wordsworth’s assistant, bringing the jewels with him. Wordsworth lived in Paris, Orleans and Blois in 1791-92 and fathered a daughter by his French lover, Annette Vallon. Like the Duc d’Orleans, he was also a convert to Robespierre’s Jacobin cause. It seems yet another odd coincidence that by September 1795, the poet and his sister were living within a few miles of Bridport – at Racedown Lodge, near Bettiscombe.

Suddenly Percy Barrett’s story about the Bridport smugglers and Robespierre does not seem so ridiculous after all.

Loders Local History Group near Bridport have been surveying what may be a smugglers’ tunnel beneath the village school. The tunnel, first discovered in 1947, is almost 21 feet long and leads from the shaft of an old well below the playground at Loders CofE Primary Academy to a vertical shaft under the school building. Lined with local stone, it is almost 5ft 4in high – big enough for an adult of average height to walk along it with a slight stoop. Chuck Willmott, who has explored the tunnel, said that unlike other Loders wells, it is not marked on old maps. This suggests its existence was concealed for some reason, perhaps lending support to the smuggling theory.

The school was built in 1869, before which two old cottages stood on the site, occupied by Thomas and Matthew Marsh. They are not known to have been related to Bridport shoemaker Sam Marsh, who was jailed for smuggling in 1824.

History Group member Roger Henwood said: ‘In the absence of any known reason for this tunnel to exist, we think that perhaps it was intended for storage of smuggled goods and as a quick means of escape should the Customs officers come calling.’ A stone ledge set into the side of the well, level with the tunnel floor, provided a perfect base for the historians’ ladder, as it would presumably have done for others 200 years ago.

In 1834 workmen found the body of a newborn baby boy in a hole in a cellar-stone used to cover the well. The suspected mother and two other women were charged with murder but later discharged.