‘The Zeebrugge Stunt’

Roger Guttridge on the centenary of the attack on Zeebrugge to prevent German U-boats entering the Channel

Published in April ’18

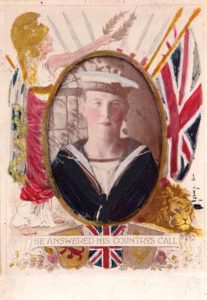

A hundred years ago this month, a young Poole sailor found himself playing a front-line role in a famous World War 1 naval operation. Twenty-year-old Able Seaman Reginald Vincent, of Princess Road, Branksome, sustained shrapnel injuries before taking part in hand-to-hand fighting, then wrote his own colourful account of the Zeebrugge Raid in his hospital bed. He sadly died almost two years later as a result of his injuries. Reg’s nine-page typescript ‘The Zeebrugge Stunt’ found its way to his brother, Bertram, and then his widow, Ivy Vincent, of Ferndown.

The Zeebrugge Raid was an attempt by the Royal Navy to stop German U-boats leaving the Belgian port by filling redundant ships with concrete and sinking them to block the entrance. But Reg knew none of that when he was selected for special training in February 1918. ‘We went on leave with the bare knowledge that we were picked for some special duty: what it was we had not the faintest idea,’ he wrote. On return from leave, they went into training with the Middlesex Regiment, ‘being perfected in bayonet fighting, bomb throwing, all the various rifle exercises and actual trench warfare. Three nights a week we practised night attacks.’

By mid-April, Reg and his comrades were on their way to Zeebrugge on HMS Vindictive. Their role was to draw the enemy’s attention while the ships were manoeuvred into position. The first attempt on 13 April was abandoned after the wind direction changed and blew away their smokescreen. They tried again on 22-23 April and Reg recalled that ‘all the lads cheered with glee’ when they got the go-ahead. ‘It’s death or glory this time,’ an officer told them. HMS Vindictive was the lead ship and was followed by cement ships, motor launches and motor scooters. The launches and scooters were there to evacuate the men from the cement ships at the critical moment.

‘During the late hours of the night we began to see heavy flashes, which we took to be from the Western front,’ Reg wrote. ‘Then we again saw our aeroplanes attacking and our monitors bombarding the Mole. Our aeroplanes were being fired hotly upon.’

In true Royal Navy tradition, the sailors were given a tot of neat rum ‘to buck our spirits up’ before entering the action. ‘Heavy smokescreens were thrown out, with great success, the wind being all in our favour,’ said Reg. ‘About 11.30 “flaming onions” or star shells burst overhead of us, lighting up all the place for about ten minutes each time and making it like daylight. At a quarter to 12 stray shots came into the smokescreen from the shore batteries, evidently to explore it and see if they could hit anything.’

Reg was posted to the Vindictive’s foremost funnel. ‘All the time shells were bursting there, but I was untouched. As soon as I joined Number One Company on the ramps, however, I got an armful of shrapnel – ten pieces were afterwards taken out. I took very little notice of this at the time – just felt the sting. My mind was more in for something else. As soon as you see blood, you want to get some of it.’

Eventually the Vindictive drew alongside the Mole and the order was given to go ‘over the top’. Reg saw many of his comrades shot, including two senior officers, who were ‘riddled with bullets’. ‘Many shots struck my rifle but none of them hurt me,’ he says. ‘I was just going round one of their pill-boxes when a huge Hun came to attack me. I engaged him and just managed to parry him off. His bayonet, however, caught the side of my nose and just missed my eye. This put a vicious feeling into me and I thought, “Well, if I don’t put him out of the way, he will me.” I caught him through the throat and passed on.’

Reg tells how he and others got behind the enemy barbed wire and machine guns, firing bombs and rifle grenades. They could see the cement ships getting into position across the mouth of the channel. Then the viaduct connecting the Mole to the Belgian mainland was blown up and ‘many enemy troops’ with it. In fact the British suffered 563 casualties during the operation – 227 dead and 356 wounded. Germany had just eight dead and 16 wounded. Unfortunately the blockships had been sunk in the wrong place and within a few days the Germans were able to open the port to submarines at high tide.

Meanwhile Reg and other survivors were given a hero’s welcome when they returned to Dover. ‘The forts cheered as we went in, as did several of our light craft which we passed,’ wrote the Parkstone seaman. ‘The ship went alongside the wharf to pick up the hospital train: the wounded were taken to hospital as quickly as possible and the dead were taken ashore. Six of us remained at Dover, thinking that as there was not much wrong with us, the men who had lost arms and legs and were severely wounded should go first.’

The following day, they returned to their barracks at Chatham. ‘As we entered the barracks we were loudly cheered by the troops there and the Admiral congratulated us upon our exploit and upon the fact that the majority of us had come back. Cinema films were taken as we marched in and the barracks band played us up to the canteen.’

By the time Reg reached the Royal Navy Hospital, it was 6 pm on 23 April, more than 24 hours after he was wounded. ‘I went under operation and it was found that I had almost put off too long having my arm attended to – I might have lost it.’ In fact, Reg was to lose more than his arm. He died in 1920 and in 1921 was posthumously awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal. His name also went into a ballot for the award of a Victoria Cross.