Dorset in close-up: galls

In the first of Paul Quagliana's two-part series, he takes a close look at some of the most fascinating structures on our garden’s plants and trees

Published in February ’18

To quote Sir David Attenborough in his book, Life in the Undergrowth: ‘Some insects… have a mysterious ability to compel a plant to produce structures that are greatly to the insects’ benefit but bring no advantage whatsoever to the plant itself. It is as if such insects are able to genetically engineer a plant’s tissues and instruct them to grow in quite different ways. Structures produced in this manner are known as galls.’

Robin’s Pincushion Gall on a rose plant caused by another wasp. Similar, but less dramatic galls on hawthorn and Norway Maple are caused by midges and aphids

Galls may be an obvious aesthetic nuisance to a keen gardener, but for many of us they pass unnoticed. Yet take a stroll with an observant eye and they can be found in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Some may find the contorted, deformed shapes with their sci-fi, alien-like mutations quite unpleasant, others may see a beauty and a fascination in them.

The Robin’s pincushion gall that favours wild roses is particularly large and pleasing to the eye, with its riot of densely packed curly fronds that encapsulate tiny wasp larvae.

It is not just insects that cause galls, though. Fungi and bacteria can also do similar work. The alder tongue gall is caused by a fungus that creates an elongated ‘tongue’, which grows from the alder catkin and assumes a scarlet hue, shrivelling to an ugly, dark relic that persists over winter. It was once unknown in the UK but it has become more common, spreading its spores far and wide on the wind.

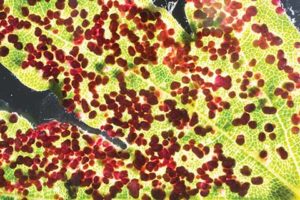

Bacteria can cause tumour-like swellings and galls to appear on various plants and trees and tiny mites less than half a millimetre smite the lime and sycamore with an outbreak of tiny, red, densely packed blobs.

The creeping thistle gall is home to a particularly attractive fly and one has to marvel at the almost perfect sphere that is created by the marble gall wasp, whose green galls harden to a shiny beige when Autumn comes. One oak tree may be infested, yet adjacent oaks may be curiously untouched. A neat round hole indicates where the grub that grew in there throughout the summer has changed into a wasp and chewed its way out.

The origin of the astonishing looking Alder Tongue Gall’s name is pretty straightforward: it grows on alder catkins and looks like a tongue

While most galls may appear to have little use other than for the creatures that produce them, the marble galls are so hard and buoyant that fishing floats are fashioned from them. However, gall wasps do not have it all their own way. In a marvellous adaption, some other wasps can detect the larva that is quietly growing in a gall, drill a hole in the gall and lay one of their own eggs that when it hatches, proceeds to eat alive the incumbent. It’s a wasp-eat-wasp world

out there.

Field Maple Galls shot against the light. Each of these galls comes from an individual mite that lived in it.

Galls and the organisms that produce them have got to be surely one of the natural world‘s most unnoticed yet incredibly well-adapted inventions. Every niche that could supply sustenance has been exploited. However, if you are a keen gardener or arborist, take heart: while their presence may be, well, galling and they may assume the role of an unwelcome guest, they are rarely damaging to the flora which they parasitise.