Veni Vidi Wimborne

Joël Lacey looks at the evidence of Roman activity around Wimborne

Published in December ’17

Within a salient of the River Stour, 1000 yards west of Wimborne Minster, there is a very special junction. It is where four (ST, SU, SY & SZ) of the fifty-six 100x100km squares that form the Ordnance Survey grid system meet. Its location and the relatively small size of Dorset are why one only needs the numerical part of an OS reference to find one’s way around Dorset rather than having to use the two letters, as none of the grid references within one of the four squares that cover Dorset is duplicated within Dorset.

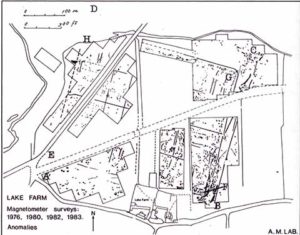

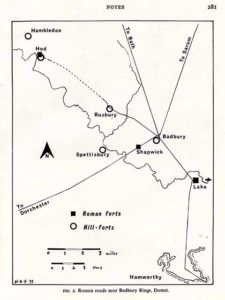

Travel northwest for 44 yards short of three miles from that OS origin point and you arrive at another very special junction, and in its time much more important than the Ordnance Survey to travellers. This second nexus, nearly 1900 years older than the first, is a crossroads from the time of the Romans and is to be found just northeast of Badbury Rings. Travel exactly half a mile due south from the OS 0,0 point, and you reach an extensive Roman fort at Lake Farm.

Although Julius Caesar made a cursory attempt to conquer Britain in 55BC, it was not until 43-44AD with Rome under the reign of Claudius, that the Romans arrived with the aim of colonising, not merely conquering. The army that did it in Dorset was the Legio II Augusta, veterans of conflicts across half of modern-day Europe. They faced the Durotriges in Dorset, a Celtic Iron-Age tribe whose dominion covered all of modern day Dorset as far as Hengistbury Head, and into East Devon, South Somerset and South Wiltshire.

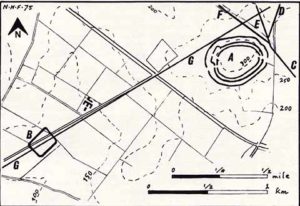

As well as the two principal (Bath to Lake and Exeter to Sarum) roads there were other subsidiary routes going off to additional forts as the invasion progressed. The figure B is the fort at Shapwick

Leading the legion was the man who would later become the Emperor Vespasian. His legion’s conquest of Dorset was achieved, according to Norman H Field – the teacher who spent decades tracing the Romans’ passage through Dorset and discoverer of the Lake Farm site – was in four stages. The first was southeast Dorset and the eastern side of Poole Harbour, up past what is now Wimborne Minster and up as far as Blandford Forum, the next stage was Purbeck, then South Dorset, Portland and Weymouth up to Sherborne, then finally West Dorset. It took them a couple of years.

Part of the reason the Romans were able to conquer and retain their acquired territory was their unparalleled control of logistics. When archaeological evidence of the means of the demise of a presumed chieftain on Hod Hill emerged, his death came after a barrage of ballista bolts was fired at the largest hut in the settlement, the only inference one can draw is that there were a number of ballistas that were used in the attack. Moving that kind of artillery on muddy animal tracks would simply not be terribly efficient, so a good military road system would make the lead up to important battles a vital logistical task.

On this larger map, we see how the crossroads at Badbury links in with the forts at Hod, Lake and Shapwick

The Roman soldiers built roads not just to speed supplies and men in support of the advancing force, they included along those roads forts both temporary and permanent to protect the roads themselves, their troops and supplies and to stop counter-attacking forces using the roads against the Romans themselves.

George Bernard Shaw stated that ‘the reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself’. The Durotriges had hillforts fortified from existing natural features, like Maiden Castle, Hod Hill, Hambledon Hill (although this is thought to have been abandoned in favour of Hod Hill prior to the Roman conflict) and Badbury Rings. The Romans just built their own forts.

The native tribes had circular homes, the Romans were all about rectangles and straight lines. Native roads followed natural features, the Romans’ went straight.

Roman forts were very often built along roads, or at crossroads, with the roads running through the fort, via asymmetric main gates, which allowed for large central buildings inside

This last fact brings us back to the intersection around Badbury Rings. There are two kinds of Roman road, the roads built for conquest and those for later, wholly civic use. As the Romans were heading, broadly speaking, west and north from their initial base, once they reached Badbury Rings, the Stour Valley opened up to them and they could deal with the natives’ hill forts one by one.

The path of the road from Badbury to Durnovaria (Dorchester) goes through a fort at Shapwick, but is thought to past-date the fort as it doesn’t go through it. In other words the fort was there before this incarnation of the road. The large settlement at Lake, however, precedes that at Shapwick, which fits in with the idea of expansion north and west from an initial base close to the coast.

According to the roman-britain.co.uk historical website (which aims to list every Roman site in Britain): ‘The first objective of the second legion after establishing its main base of operations at Lake Farm, was the reduction of the nearby hillforts at Badbury Rings and Spettisbury [sic] Rings, which were situated to either side of the River Stour. The fall of these two British strongholds displaced a substantial number of native Britons, who were to form the nucleus of the settlement at Vindocladia’.

Roman Britain places Vindocladia at the national grid reference ST9502, a mile west and 0.6 mile south of Badbury Rings. When one considers the great yawning gaps between other Roman forts in Dorset and also the relatively little evidence there has been for other Roman roads throughout the county, that there should be so much activity around Wimborne, with forts and roads (both military and civic) indicates just how crucial a role this nexus played in the early stages of the conquest of the Durotriges by the Romans.

After temporary wooden forts were built, the Romans would either raze them or replace or augment them with more permanent structures

One of the most interesting facts is that Roman encampments, places used for over-wintering of troops when they were not on campaigns, or for temporary guarding whilst they were on campaigns, would be razed by the Romans afterwards, the earth and stones from the banks would be used to refill the ditches. This practise means that the forts that are left, like the fort at Lake, were important permanent structures.

The settlement of Wimborne Minster itself does not obviously date back to Roman times, but the area’s importance, its position on the Roman roads network and its location in the fertile meadows on the Stour, made it (and still make it) attractive to settlers and travellers.