Literary links of every kind

Joël Lacey visit’s Wimborne Minster’s fascinating chained library

Published in September ’17

How well do you really know Dorset? How about a quick quiz question to find out? What do the following things have in common: tobacco, the ceding of Gibraltar to the newly named Great Britain and a lady named Phyllis wanting to look her best? If you answered Matthew Prior of Wimborne Minster, congratulations; if you did not, please read on.

Leading from what is now the choristers’ practice room in Wimborne Minster, there is a stone spiral staircase leading up to what was once the Minster’s treasury. It is not the conventional clockwise direction of travel on a spiral staircase, but rather an ‘ecclesiastic’ staircase, where right-handed swordsmen from above could easily hold off those attempting to climb the stairs, while those climbing from below would have to fight left-handed, or very disadvantageously right-handed.

Unfortunately, even this architectural measure did not prevent the agents of Henry VIII from taking the Minster’s collection of relics and precious metal reliquaries, nor the commissioners of his son, Edward VI, from nicking the Minster’s best silver a few years later. With the treasury hardly now meriting its name, it was principally used as a store from the mid-16th century until 1685, when the library first came into being

The cost of its construction was £25, but what were the books and where did they come from?

The answer is that they were religious texts in Greek and Latin with contemporary remarks from the leading religious thinkers of the time (‘Fathers and Commentators’) and they came as a gift from Reverend William Stone, twice named as a papist in Parliament, a former Presbyter of the Wimborne church, Headmaster of the Grammar School and later Principal of New Inn Hall in Oxford. What these ninety books were not for, however, was public consumption. It would only be a decade later, once the library’s second great benefactor, Roger Gillingham, gave around the same number of books as Rev. Stone, that some element of public access became available.

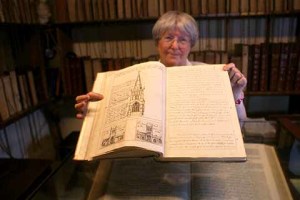

Librarian Judith Monds holding the history of Wimborne Minster open at the page showing the spire that used to sit atop one of the Minster’s towers

It still wasn’t for hoi polloi, though, as Judith Monds, head of Wimborne Minster’s library team explains: ‘You had to be a “shopkeeper, or the better class of person” to get in.’ As this pretty much represented all the townspeople who would be likely to be able to read at the time, it was probably less about class than literacy. ‘Gillingham suggested that the books be chained so they wouldn’t have people taking them home and forgetting to bring them back.’

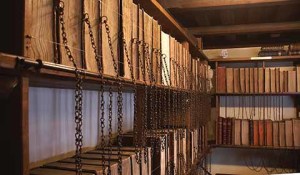

As the chains were an addition that came after the installation of the library, it does not have the angled desks normally associated with the few other chained libraries still in existence*. The chains would initially have been hand-forged and hand-brazed or welded, but the ones now used for all but four of Wimborne’s books are made from knotted chain made of wire, and so likely mid-19th-century in origin, not 17th-century as the process to produce knotted links was not patented until the late 1700s and the Minster, including its library, was ‘restored’ in the 1850s.

This time, Judith shows the twin towers that we more readily associate with Wimborne Minster these days

At Wimborne you have to locate your lectern in front of the bookcase within which your book is located. If there were not alarm wires running in front of the volumes, one would then reach up and pick up the book and then place it on the lectern to read it. As can be seen from the wider shots of the Chained Library (and it is a scene repeated in others, too) the books are by and large placed spine to the wall so that the cover to which the chain is chained doesn’t foul the chain as one is picking the book up to put it on the lectern, nor the chain foul on other books when the volume is put back. For this reason, some of the books are marked on their page edges, some in Roman numerals, some in Arabic number, so they can be identified without being taken down… at least, that was the theory.

The first list of books in the library was made by Nicholas Russell (of whom more a little later) and was created in 1725. It identified 285 volumes, with 111 numbers. Some numbers were used up to four times, which is not quite the model of clarity one might have hoped for. By 1863 a new updated list, which referred to the then still legible 1725 list, was produced. Unfortunately for modern cataloguers, the 1725 list is missing the pages for volumes starting with the letters A, W, Y and Z, those for U and V are damaged and that for B near illegible. By 2007, though, the information on these pages had all been re-created by one means or another.

Once one has feasted on the history and mechanics of the chained library, one must come to the thing which defines the quality of any library: its stock. Here, too, Wimborne is blessed, and not merely with the aforementioned ‘Fathers and Commentators’: there are some absolute treasures.

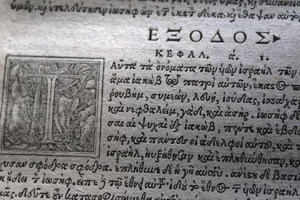

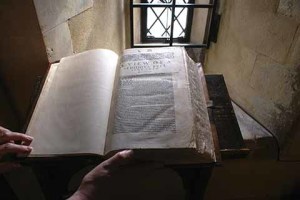

The oldest book is Regimen Animarum – a 1343 manuscript offering guidance for souls and written on vellum. The oldest printed book is of the works of St Anselm and was printed in Basle in 1495, just 55 years after Gutenberg first used a printing press to produce a Bible. There is the incredibly rare blind-stamped binding of a 1532 volume of Theophylacti … in quatuor Euangelia, which was given by Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon; the binding bears his Tudor rose and her pomegranate symbol. Quite what she would have made of the work, which consists of commentaries (ie. criticisms) on the Catholic view of the gospels made by Johannes Oecolampadius, a German Protestant reformer, is not recorded; it is unlikely it ever reached her library.

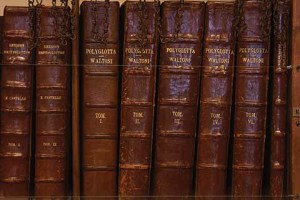

There is the astonishing Biblia Sacra Polyglotta by Walton (published in 1653-57 in six volumes at public subscription for £10 per volume or all six for £50 – a 16.66% saving but still, at today’s prices, an investment of over £10,000). This book, along with the Lexicon Heptaglotta by Edmund Castle, is an attempt to expose and eradicate inconsistencies brought about through translation in the Bible by printing eastern and near-eastern languages (Hebrew, Arabic, Samarian, Illyrian, Georgian, Coptic {Egyptian}, Syriac, Ethiopiac) alongside the Greek, as well as the Vulgate Latin 4th-century translation and commentaries on the other languages, although not all the languages are used in all books. So important was the book considered that it was approved of by both the puritan Cromwell and the then-in-exile Prince (later King) Charles (II) who, on his deathbed at least, was a Catholic.

‘…there came to my hand, a copy of a bull lately sent into this Realm by the Bishop of Rome’. As this page was headlined ‘A view of a seditious Bull…’, we can presume this was written after Henry VIII had petitioned unsuccessfully for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon

On a more secular level, Walter Raleigh’s The History of the World was written during his time in the Tower of London, not when he was at Sherborne. Eighty pages of the book bear burn marks that have been repaired or the pages replaced. The damage is sometimes ascribed to Matthew Prior, later negotiator of and signatory to the Treaties of Utrecht – popularly known as ‘Matt’s Peace’ which, amongst other issues, had the Spanish cede Gibraltar to Great Britain. Sadly, as he was the son of a joiner who was a dissenter, he probably wouldn’t have even entered the Minster library and had probably left for his uncle’s house in London by the time the damage was done anyway.

Despite the books of global importance and national significance, it is two books of local origin that might well be the most interesting in the collection. The first is a History of Wimborne by the aforementioned, list-making, Nicholas Russell. In this wonderfully illustrated book are pictures of the Minster, including of its stone spire and the attendant miracle of that object’s collapse without a single casualty, and programmes of works at various times.

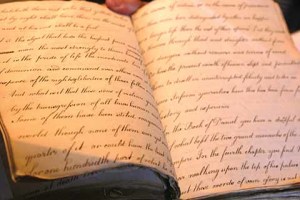

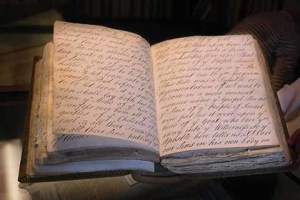

The most charming book, though, is not really a book at all, so much as a collection of the handwritten sermons of various priests through the ages. Some obviously sought and received divine inspiration, as their writing flows unhindered across the page. As all writers will sympathise, though, others clearly struggled; their sermons bear the scars of revisions, angry crossings out and last-minute second thoughts.

Wimborne Chained Library is open from Easter to the end of October. Mon 2.00 to 4.00; Tuesday to Friday 10.30-12.30, 2.00-4.00; 1st Saturday in the Month 10.30 to 12.30.

* England’s Chained Libraries

Other than Wimborne Minster’s (around 400 books, 150 chained), there are six chained libraries of note in England. The largest chained collection after Hereford Cathedral (1500 chained books) is Wells Cathedral. Trinity Hall in Cambridge still has pretty much all its original furniture while the Royal Grammar School in Guildford is currently re-chaining some unchained books to boost itself up the chaining charts, while St Wulfram’s Church in Grantham (with 80 chained books) is still bigger than the kitchen cupboard-sized chained library at Chelsea Old Church (five chained volumes).