The problem with the past; it keeps getting bigger

Brian Cormack looks at the work of the Windrose Rural Media Trust from Bourton near Gillingham

Published in August ’15

A gentle wave of approving murmurs punctures the rapt silence in the Stour Hall at The Exchange in Sturminster Newton where a sell-out audience is watching a series of restored films, some of them more than a century old, that reveal the Dorset folk of yesterday are not so very different from how we are today.

‘The past and future are one great stream,’ goes the narration, which reminds us we are living on the tip of history, bridging the past and the future thanks to the miracle of memory in this case aided by film. Folk songs, many of them traditional to Dorset, are performed live on stage by singer Amanda Boyd and instrumentalist John Shaw and fortify the connection to the past.

For the most part the show, Those Were The Days My Friends is a shared experience of gentle nostalgia for an age most of the audience have only heard stories about. Few have any direct link to the films of Iwerne Minster in 1918, of Verwood Pottery the year before, or even the coronation celebrations in Blandford in 1937. However, a 1966 film, in colour and with an implausibly cheerful soundtrack, that captures the end of the old Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway line produces a few more animated mumbles that begin ‘I remember…’. Towards the end of the evening, a piece about the final day of the Sturminster Newton cattle market in 1998 noticeably changes the mood in the audience. ‘’Tis a scandal,’ someone tuts; ‘Shame, shame,’ stage whispers another. That we are sat in a building that occupies the very place that stirs such emotions only heightens the sense of loss it seems.

The show is the last in a series of presentations by the Windrose Rural Media Trust and financed by the Arts Council. An application by the Trust for further funding is underway and the support of the community in coming out to see it, together with the warm reaction of the audience, fuel hopes for its success.

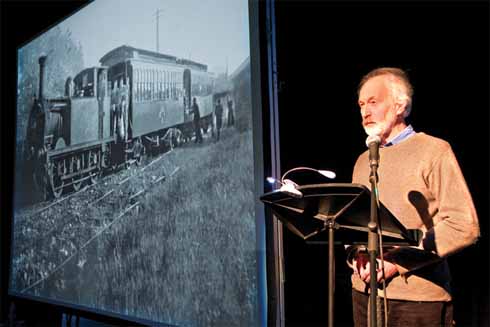

‘Tens of thousands of people have seen Those Were the Days My Friends and the latest series of eight shows was the first time we have had money from the Arts Council – it usually only likes to give money to its friends,’ says Trevor Bailey, the show’s narrator and a director and founder of Windrose.

Singer Amanda Boyd and guitarist Nick Cocking accompany archive silent film in Those Were The Days My Friends (James Macalpine)

Formed some 30 years ago to act as a video and television production unit for the benefit of the rural community, Windrose Rural Media Trust, or Trilith as it was originally known, now stands at a crossroads created by its own success. Not only does it hold a substantial archive of old film, it has hundreds of hours of raw footage shot for its own productions. And the problem with the past is that it keeps getting bigger.

‘Part of the remit is to find new ways of using the archive so we don’t just engage the casual and the curious, but also the people in those communities today because they are the ones that know the stories better than anyone. They’ll spot something in a film and will tell you stories related to it. Similarly, tracing the descendants of the people in the films, talking to their families, or finding the people that do their jobs today, you get wonderful tales that combine to tell the story of change in the countryside.

‘Much of the footage is on VHS tape, which is obsolete and was never a permanent medium anyway, but it isn’t simply a case of transferring it to DVD or digitising it. We are working with Dorset History Centre to futureproof the material so that it can be correctly stored in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment and in a form that can be easily migrated from one digital system to another.

‘That means it all needs to be viewed and prioritised before it can be properly archived… and I’m 68!’

Windrose is a registered charity and a key function of Trevor’s role as Trustee has been to seek funding for its many projects, including that of securing the archive and respecting the intricate network of ownership rights. But while a vital part of the Trust’s work is the saving and copying of old cine films so they can be accessed by the public it was originally conceived as a production unit and for most of its existence has made programmes in partnership with community groups and local authorities.

By far its biggest project, Farm Radio commanded funding in excess of £700,000 and established an internet radio station aimed at small family farms and people working in related sectors. By the time it ceased broadcasting in 2009 it had established links with community broadcasters in Ireland, Australia and Malawi and found a loyal listenership in Japan.

‘It was quite bizarre, we even had a Japanese television crew follow us around for a few days to make a documentary about us. One of the most successful things about Farm Radio was Future Farming Voices in which young people made programmes about their experience of farming and talked to older generations about their jobs – I was unsure about the cross-generational approach, but it worked far better than I thought it would because they had farming in common.’

Debra Hearne oversees an interview with ‘Thurston’, a Saxon chief following his victory in battle against the Vikings on the South Dorset Ridgeway (actually the Wey Valley School playground!)

Former BBC presenters Debra Hearne and Ali Grant are continuing the commitment to audio media by training young people in radio journalism and production. Working in groups the trainees have been focusing on heritage subjects relating to the South Dorset Ridgeway Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, interviewing older people to create oral histories and audio trails, which can be downloaded from the Dorset AONB website.

A broadcaster and journalist himself, Trevor’s motivation for Windrose stems from an abiding passion for the countryside and a sense that country voices are routinely misrepresented in the media.

‘I have a feeling that the media uses real people’s stories as fuel and takes them away, but it has always been our intention to add to those stories and the communities they come from. For instance, one of our projects Dope Under Thorncombe is a silent film from the 1930s made by a Bridport man called Frank Trevett. We commissioned a new musical score for the film, which created an opportunity for a young composer called Rachel Leach, and Frank Trevett’s daughter Vivienne Smith gave a short talk before the live performances of the film and music, which went down very well at Bridport Arts Centre.’

The Trust has unearthed many rare gems, but none more exceptional than The Tale of the Amplion, the only known animation by revered illustrator William Heath Robinson. It was an advertisement for an early wireless loudspeaker and, in Heath Robinson’s trademark quirky fashion, showed the animated speaker grow into a real lion and gobble up a listener.

‘It was all quite surreal,’ confirms Trevor, ‘but the thing was nobody knew about it, not even the Heath Robinson Trust or his surviving children. It was found in a box under a workbench in a wooden lean-to by Frank Marshall whose family had run an electrical business on Portland for years. In the 1920s they had shown the film in local cinemas. It was a nitrate film so quite unstable, but we sent it to the National Archive for restoration and made a film about it.’

The Windrose archive really comes into its own when used to tell contemporary stories, such as the 1918 film of Iwerne Minster made by the Ministry of Information at the behest of James Ismay, the lord of the manor. The film captures two days in the life of the village and was intended to reassure troops that all was well on the

Home Front.

‘We were able to trace the descendants of some of the people in the film and interview them. Some of them we got to literally walk in the same footsteps and, I think it was the grandson of the shepherd, but when we superimposed the old images with the new you could clearly see he had exactly the same walk.

‘I think only five of the families in the original film still had relatives in the village, which tells its own story. Ismay was a benevolent paternalist and wanted to keep his community together. Reading his letters over the images makes for a powerful film that gives a long perspective on how the countryside has changed over the last century and the process is continuing.

‘We need to get back into production again because there are important stories to be told about the countryside,’ says Trevor. ‘Issues such as isolation, the fragmentation of the rural economy, the failure of small farms especially dairy farming, the crisis in house prices, rural schools, transport, employment. All of these things continue to impact on the countryside.’

They do and to one extent or another probably always have. Perhaps the greatest lesson of the past only proves the cliché that the more things change the more they stay the same. ◗

❱ To see whether there are any films for your area visit www.closeencounters-mediatrail.org.uk contact or support Windrose Media Trust at Corner Cottage, Brickyard Lane, Bourton, Gillingham SP8 5PJ, 01747 840750, email: tbailey352@btinternet.com