When Dorset went to Waterloo

David Callaghan looks at Dorset’s enduring contribution to the final defeat of Napoleon

Published in June ’15

The Battle of Waterloo, the bicentenary of which is on 18 June, remains a defining moment in European history. It brought to an end 23 years of global conflict against the expansionist French, secured Britain’s empire and ushered in almost 50 years of peace in Europe.

It was at no small cost, though, as nearly 50,000 men were killed or wounded that day as the Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon Bonaparte with the late arrival of the Prussian army. Four days later the first reports appeared in The Times and Britain celebrated. In Dorset, as elsewhere, public gestures were made to commemorate the victory and the once tiny village of Waterloo – now a large housing estate – near Broadstone owes its name to the victory, as does Waterloo Mill at Gillingham and any number of Waterloo and Wellington Roads. It’s not clear when The Waterloo pub in Weymouth was named, or when the Duke of Wellington was adopted as the name of the 16th century Wareham pub, or its slightly later namesake in Christchurch, but a rash of re-namings also followed the battle’s 50th anniversary in 1865.

The Duke of Wellington reviewed troops at Blandford Camp in 1815 before setting out on the campaign that ended at Waterloo and Dorset men enlisted in significant numbers, not least in Bishop’s Caundle where the local inn – now called The Trooper – became a temporary recruitment station, but as the Dorsetshire Regiment wasn’t founded until 1881 with the amalgamation of the 39th and 45th Regiments of Foot*, neither of which had any particular connection to the county, their stories are scattered throughout Wellington’s army.

William Lawrence as imagined by military artist Dawn Waring for A Dorset Soldier, the 1995 publication of his autobiography edited by Eileen Hathaway and printed by Spellmount Publishers

Perhaps the best known is that of William Lawrence, whose autobiography A Dorset Soldier was last published in 1995. Born in 1791 in Bryant’s Piddle (as Briantspuddle then was), the son of a farm labourer, at the age of 14 he was apprenticed to Studland builder Henry Bush. To escape his master’s cruelty Lawrence ran away to Poole and found work on the Newfoundland packets before returning and eventually enlisting in the 40th Regiment of Foot shortly before it sailed for South America in 1806.

His stories spare the reader few horrors of war, but neither do they embroider it. At Waterloo he relates seeing his captain’s head blown off in exactly the same tone as he recalls preparing a feast of ham and chicken taken from the enemy, breaking off from his culinary task to attend a “Frenchman groaning under a cannon”.

During the subsequent march of Wellington’s army on Paris, Lawrence met and married a French girl, Clotilde Clairet, who continued to follow him on his travels until he was finally discharged from the army in 1821. The Lawrences spent a brief spell in Affpuddle, then moved to Studland where William drifted between trades until he took on the tenancy of the New Inn in 1844 and renamed it the Wellington Inn. Famed for his anecdotes, he ran the pub until he retired in 1856, three years after Clotilde’s death.

A year or so later, William set about dictating his life story (he was illiterate) and on his death in 1869 bequeathed the manuscript to his friend George Bankes, the local landowner and MP. Lawrence was buried with Clotilde in St Nicholas’ Church at Studland and volunteers granted his wish for a military send off by firing a volley over their grave, which stands just outside the porch.

Few, if any, other stories from the ranks are as well documented as that of William Lawrence. For instance, little else is known about John Stacey, who was born in 1794 at Milborne Port, enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1812 and fought at Waterloo before being discharged on medical grounds in 1838. Further mystery surrounds Private Peter Burbridge of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards who enlisted in 1809 at the age of 20 and was discharged in November 1815 after losing the use of his elbow when wounded at Waterloo. It seems he may never have received his medal because although the award is confirmed by the Waterloo Medal Roll, the actual medal was incorrectly marked 2nd Battalion and returned to Horse Guards where it turned up with those for others deemed unfit for service. Burbridge lived at Loders near Bridport and died on 30 December 1870.

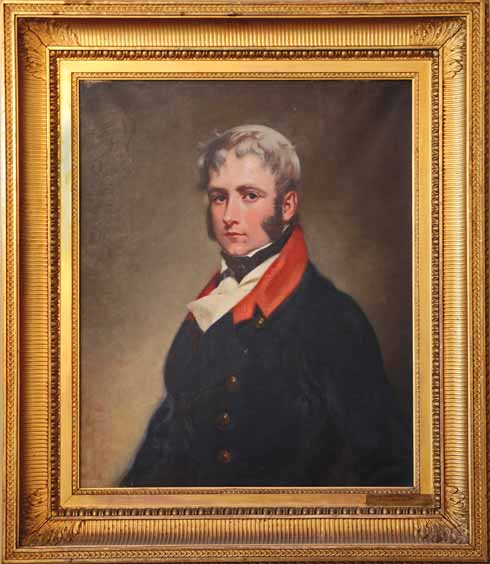

Henry William Paget (by William Salter) in the National Portrait Gallery © National Portrait Gallery, London

At the other end of the military hierarchy and one who was handsomely rewarded for his action at Waterloo was Henry Paget, the Earl of Uxbridge, who had inherited Stalbridge Park in 1812. Already a noted military leader, he was at the head of a decisive cavalry charge that in part routed the French army at Waterloo. Famously, not long after he was hit by a French cannon ball. Turning to the nearby Wellington he cried: ‘By God, sir, I’ve lost my leg!’ To which Wellington replied: ‘By God, sir, so you have!’ For some considerable time his amputated limb served as a macabre tourist attraction in the village of Waterloo, while the saw used to remove it is held by the National Army Museum.

He had little time for Stalbridge though and in 1823 the old house was demolished and the stone used to build Stalbridge Park Farmhouse, which still stands. Paget, who was made Marquess of Anglesey after Waterloo, did however help establish the nationally noted Anglesea Cricket Club in the Park in 1825.

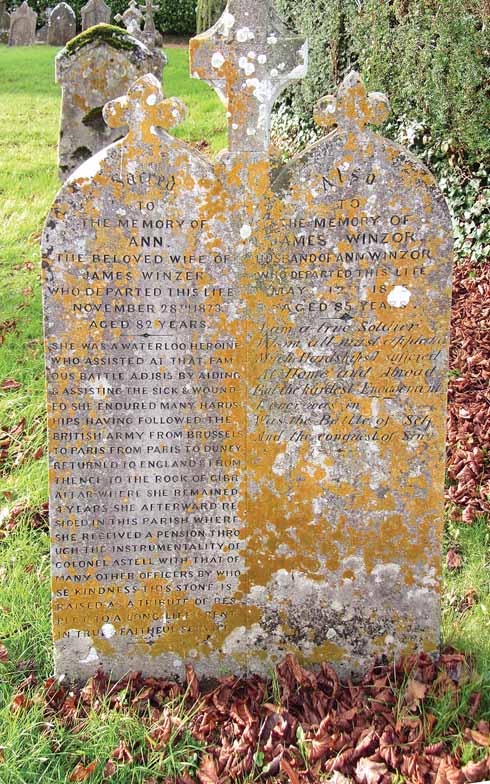

But for all his stiff upper lip and derring-do Paget is arguably outdone in the bravery stakes by the courage of Ann Winzer, dubbed the Heroine of Waterloo. Born in Fordington where she married James Winzer, a soldier in the Light Dragoons, on 1 April 1811, Ann joined her husband as his regiment was posted Brussels to protect the Belgian capital ahead of the coming engagement with Napoleon. She then followed him to the battleground at Waterloo where she distinguished herself tending to scores of sick and wounded soldiers both during the battle and afterwards on the long road to Paris.

Acting some 40 years before Florence Nightingale took her party of nurses to the Crimea, Ann’s feats are recorded on her impressive headstone at St Mary’s Church in Piddlehinton, which was paid for by a group of army officers, notably Lt Col Charles Astell JP who lived at nearby West Lodge and had petitioned for Ann to receive a military pension in her own right in recognition of her services. Ann died in 1873 and James 18 months later.

Also in Brussels were Edward and Mary Greathed of Uddens House in Ferndown. A former captain of the 3rd Dragoon Guards, Greathed did not hold a current commission, but was probably in Brussels on government business and was invited to the Duchess of Richmond’s famous ball on 15 June, three days before Waterloo, along with Wellington and nearly all his senior officers. The ball has gone down in history as the culmination of Wellington’s brand of business-as-usual psychological warfare and is where he received news of Napoleon’s invasion of Belgium. Unflustered Wellington remained at the ball then, just before retiring to bed, met with his officers and ordered his army to march out of Brussels to meet the French.

As peace returned to Europe, Greathed spent many of his later years abroad and received favour from Charles X of France. His portrait is in the Priest’s House Museum in Wimborne as is his daughter Mary’s diary.

Studland in the 1880s. Looking down Manor Road towards Little Beach, the cottage on the left is the original (now demolished) village pub, the New Inn, renamed the Wellington Inn by William Lawrence. On the right is the building now known as the Bankes Arms. In the 1880s it was in use as a pub then called, accurately if confusingly, the New Inn.

A version of the Duchess of Richmond’s Ball is recounted in Byron’s poem The Eve of Waterloo and it seems just as fitting that Dorset’s two best-known literary sons should also have drawn inspiration from the battle. Published in A Second Collection of Poems in the Dorset Dialect some 50 years after the battle, Bishop’s Caundle by William Barnes relates the victory celebrations he witnessed as a teenager in the village.

Finally, the young Thomas Hardy would have grown up hearing the local fears of a French invasion from those for whom Waterloo was still in living memory. Years later he visited the battleground while researching The Dynasts, his epic verse drama of the Napoleonic Wars published in three parts in 1904, 1906 and 1908. Reflective, sometimes satirical and at others pessimistic, it includes the poem The Field of Waterloo in which he describes the brutality from the perspective of plants and wildlife. It all but prophesies future horrors as Europe descended into the Great War, even more so given Hardy’s acknowledged influence on war poets such as Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon, whom he knew well.

That Hardy was writing about Waterloo almost a century after Wellington’s victory is ample illustration of its significance. The allied armies of Britain, Prussia, the Low Countries and Russia represented the first time modern European nations had come together to defeat a common enemy, an action that may still serve to remind us that European countries tend to fare better when banded together than on their own. ◗

* Although the 39th arrived too late to join the battle and the 54th were deployed 10 miles away at Hal to cover the Channel ports, 603 of its soldiers were awarded the Waterloo Medal, the first to be issued to all ranks in the British Army who fought in a specific action.

Bishop’s Caundle (excerpt)

At peace day, who but we should goo

To Caundle vor an’ hour or two:

As gay a day as ever broke

Above the heads o’ Caundle vo’k,

Vor peace, a-come vor all, did come

To them wi’ two new friends at hwome.

Zoo while we kept, wi’ nimble peäce,

The wold dun tow’r avore our feace,

The air, at last, begun to come

Wi’ drubbens ov a beaten drum;

An’ then we heard the horns’ loud droats

Play off a tuen’s upper notes;

An’ then agean a-risen chearm

Vrom tongues o’ people in a zwarm:

An’ zoo, at last, we stood among

The merry feaces o’ the drong.

An’ there, wi’ garlands all a-tied

In wreaths an’ bows on every zide,

An’ color’d flags, a fluttren high

An’ bright avore the sheenen sky,

The very guide-post wer a-drest

Wi’ posies on his earms an’ breast.

At last, the vo’k zwarm’d in by scores

An’ hundreds droo the high barn-doors,

To dine on English feare, in ranks,

A-zot on chairs, or stools, or planks,

By bwoards a-reachen, row an’ row,

Wi’ cloths so white as driven snow.