Weymouth’s Wilberforce

The abolition of slavery is usually attributed to William Wilberforce, but the man who turned his dream into reality was a Weymouth MP, Thomas Fowell Buxton. Tony Burton-Page tells the story of a forgotten Dorset hero.

Published in December ’12

It is not always wise to dig too deeply into the past of any port. Dark deeds lurk very near the surface of any coastal town with a seafaring history. Many of these are linked with smuggling of some sort, but even trade which was legally sanctioned seems unpalatable to a 21st-century conscience: in particular, the slave trade has cast a grim shadow on the reputation of such venerable ports as Liverpool, Bristol and London. Even some smaller ports played a part in this despicable trafficking – ships from Poole, Lyme Regis and Weymouth made the terrible journey across the Atlantic from Africa to the West Indies.

But of all the ports tarnished in this way, Weymouth has the greatest justification in claiming that it redeemed itself. For its townspeople elected – and then re-elected six times over the next two decades – one of the great champions of the anti-slavery movement in Great Britain: Thomas Fowell Buxton. The name forever associated with that movement is William Wilberforce, the strength of whose fame has led to Buxton being forgotten by all but students of 19th-century history and some dedicated Weymouth campaigners. And yet his image is at our fingertips every time we pick up a £5 note: he is the man in glasses on the extreme left of the illustration on the back, which features the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry reading to prisoners at Newgate.

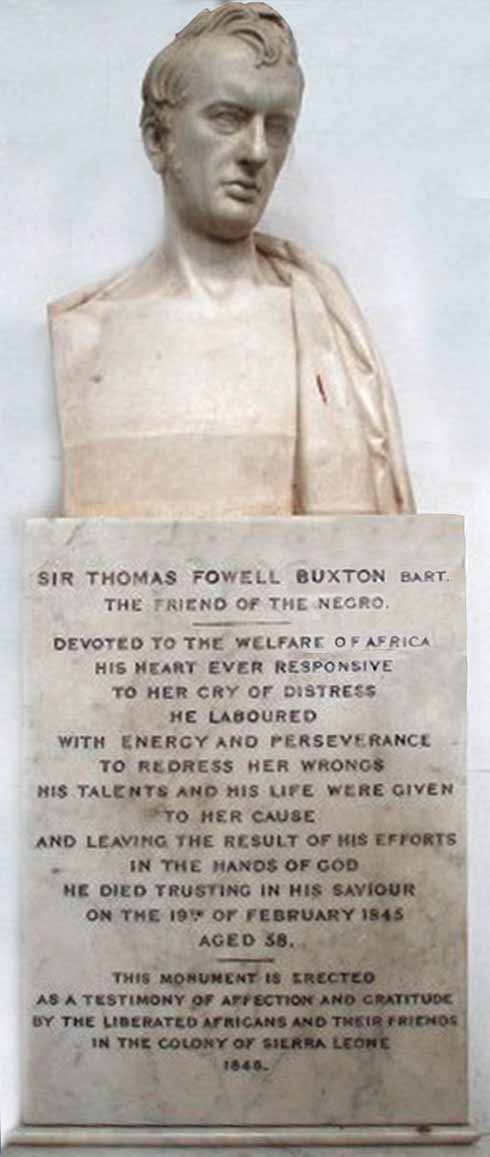

Wilberforce is to this day the best known of the anti-slave trade campaigners, primarily because of his success in getting the Slave Trade Act on the statute book in 1807. But the Act only abolished the trade: it did not abolish slavery itself, which remained legal in most of the British Empire until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, by which time Wilberforce had retired from Parliament and Buxton had taken over as the leader of the campaign there. Ironically, Wilberforce died before the Abolition Bill was passed, and it was more than a year after his death that slavery was actually abolished, on 1 August 1834. This may seem disconcertingly recent, but in Britain itself slavery had been illegal since the Council of London in 1102, a ruling strengthened by Magna Carta in 1215; and in 1701 the Lord Chief Justice had decreed that any slave became free as soon as he set foot in England.

Nevertheless, it needed men like Thomas Buxton to disseminate the concept of emancipation beyond the shores of Britain. As early as 1816, Wilberforce had become aware of Buxton’s talent and written him what we would now call a fan letter. By 1821 he recognised his suitability as his successor. In a letter written in May that year, he asked him to form an alliance with him ‘that may truly be termed holy’ and if Wilberforce were unable to finish ‘the war against the abuses of our criminal law’ that Buxton ‘would continue to prosecute it’.

Buxton came from a well-off background, having connections with the Hanbury brewing dynasty, an old Essex family who had a seat at Holfield Grange. He was born in the village of Castle Hedingham on 1 April 1786. His father (also called Thomas Fowell Buxton, in the fashion of the times apparently designed to confuse biographers) was said to have been High Sheriff of Essex, although his name does not appear in the official lists. But Thomas junior did not know him for long. At the age of four, he was sent to a boarding-school in Kingston-upon-Thames, and he did not leave it until the sudden death of his father at the early age of thirty-seven. Thomas was then seven years old and, as the eldest son (there were four other children), he became the head of the family at that tender age. Adulthood was thus thrust upon him: a contemporary report said of him that ‘he never was a child; he was a man when in petticoats.’

Belfield House, beloved home of Buxton's grandmother, was once a country home, but is now a part of the suburb of Wyke Regis (picture: Roger Dyson)

At about this time Thomas was taken out of the school at Kingston, where he had apparently been ill-treated and malnourished; indeed, he suffered from weak health for all of his life. He was moved to a school in Greenwich run by Dr Charles Burney, son of the identically named music historian and brother of the novelist Fanny Burney, and there he found a more congenial environment. Life at home was dominated by the stern Quaker principles of his mother, although he never resented this: many years later, he wrote that he constantly felt ‘the effects of principles planted early by you in my mind’. But the happiest times of his childhood were the days spent at his grandmother’s country house near Weymouth, Belfield. Nowadays it is in the residential area of Wyke Regis, but in the early 19th century it was surrounded by lawns and gardens and had beautiful views of Weymouth Bay and the Isle of Portland. The house has been described as Weymouth’s finest and most important Georgian house and has recently undergone an award-winning restoration. Thomas was enchanted by Belfield and he never lost his love for the place; when, decades later, he began thinking about standing for Parliament, it was almost inevitable that he would choose Weymouth as his constituency.

Before that time, however, he was completing his education. He had made little progress at school but a visit to the house of his friend John Gurney inspired him to greater academic efforts. John and his ten siblings were given instruction on a daily basis, either at the village school or at home, and Thomas was struck by their intellectual curiosity. This was not the family’s only influence on his life: John’s sister Elizabeth was the future Elizabeth Fry, prison reformer and philanthropist, and her sister Hannah would become Thomas’s wife in 1807. But a more immediate effect was a new-found enthusiasm for his own educational future, and he set his sights on going to Trinity College, Dublin. This was not as strange a choice as it might seem, as he was due to inherit property in Ireland. In fact, this never materialised, but Thomas did not waste his time at Trinity: he graduated with distinction, gaining the university’s highest honour, the gold star. A month after graduating, he married Hannah Gurney. They spent their first few months together in a cottage near his beloved Belfield.

Next year, at the age of 22, he started his first job. This was at Truman, Hanbury and Co., the famous brewery in Spitalfields run by Thomas’s uncle, Sampson Hanbury. He worked there for the next ten years, gradually introducing many changes to improve both the efficiency of the firm and the working conditions of its workers, including a scheme to ensure that they could read and write.

His zeal for social reform was manifest further when he joined the campaign for the relief of London weavers who were on the poverty line because of the new factories. His speech at Mansion House in 1816 raised £43,369 for a benevolent fund for them and was the inspiration for Wilberforce’s fan letter. As his posthumous biography (by his son) puts it, ‘Mr. Buxton’s public career may be said to have commenced.’ The next year he joined his sister-in-law Elizabeth Fry’s Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners in Newgate, and in 1818 he stood as an independent candidate for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in the general election. Winning six further elections, he was their MP until 1837.

Buxton appears on the very left of the Elizabeth Fry side of the current five pound note (picture: Bank of England)

He summed up his stance in a contemporary letter. ‘I care but little about party politics. I vote as I like… but I feel the greatest interest on subjects such as the Slave Trade, the condition of the poor, prisons, and Criminal Law: to these I devote myself, and should be quite content never to give another vote upon a party question.’ He was as good as his words. He campaigned for a reduction in the number of crimes that had the death penalty, including forgery; he helped to bring an end to the practice (known as ‘suttee’) of the burning of Indian women at their husband’s death; he even supported Catholic emancipation in Ireland, a highly risky and controversial position.

But it was the abolition of slavery which absorbed most his time and energy during his parliamentary career. After assuming the leadership of the anti-slavery campaign in parliament from Wilberforce in 1821, Buxton submitted a motion that ‘slavery is repugnant to the principles of the British constitution and of the Christian religion; and ought to be gradually abolished throughout the British Colonies.’ But by 1830 nothing had been done, so he organised petition after petition. he managed to persuade Parliament to vote for his bill by agreeing that slave-owners should be compensated, which angered many abolitionists. He received vitriolic letters from both sides, which took a toll on his health, but eventually his cause won the day.

A silver snuffbox presented to Thomas Fowell Buxton when he lost the election of 1837 and left Parliament for good

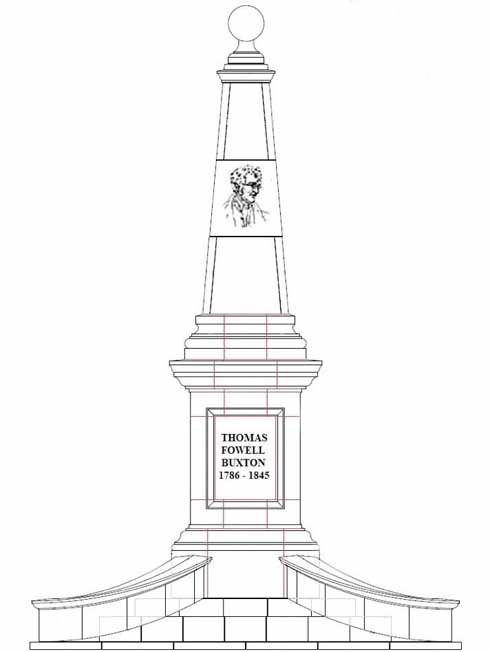

He left Parliament in 1837 but continued to press for further improvements in Africa. His health declined and he died aged only 58 in 1845. But Weymouth’s Thomas Fowell Buxton Society has ensured that there will be a memorial to this hero, with a monument planned for Manor Roundabout at the end of the new relief road – a fitting position at the gateway to Weymouth.